How Virtual Reality is Making Mobility Accessible for Everyone: Podcast Script

The promise of technology is to make life easier for everyone. In order to achieve that, designers have to understand the full range of the audience they’re designing for. Nowhere is that more challenging than when trying to understand the diversity of mental and physical disabilities that prevent people from accessing independent mobility.

Traditional design methods can’t possibly take into account the individual challenges that represent this segment of the population. In order to understand the needs of people with disabilities, we have to think outside of the box. Designers have to consider a wide range of options for operations like lifting a handle, opening a door, starting an engine, and safely operating a vehicle.

In this episode of the Women Driving the Future series, Ed Bernardon interviews Sofia Lewandowski. She’s a Senior UX Researcher, IoT & Industry 4.0 at FactoryPal, where she works directly on the factory floor to help design and create vehicles that work for everyone. Rather than assuming an understanding of the unique needs of the disabled, Lewandowski created a virtual environment that enabled people with a wide range of disabilities to be a part of the design process.

We talk about how she came up with the idea of combining virtual reality and autonomy, and how the consumers it benefits are instrumental in making these designs function for everyone. You’ll also hear about the use cases where the virtual design process has been successful on the ground.

This is the transcript of the episode.

Ed Bernardon: When we think about how we move around a city, what do we value? Efficiency in getting from A to B, the Options available to us? When assessing these options We might not consider accessibility to be important unless we recently sprained an ankle and have to account for a pair of crutches or maybe we have a physical or mental disability.

The ability to access an option that suit our specific needs best is really the first hurdle. To provide greater access for all of us, transportation designers have to widen their scope with a more empathetic lens with greater inclusivity in mind. This requires user involvement from the start. Now, in many ways the challenges of moving people from point A to point B in a city are similar to those in a factory where we want to efficiently move products on a production lines from point A to point B especially when you consider how factories and our city streets are becoming more and more automated.

Today’s guest has unique insight into designing transportation that is more inclusive for everyone, and how this design insight can be applied to the factory floor.

-intro music-

Welcome to the Future Car Podcast. I’m Ed Bernardon, from Siemens Digital Industry Software. In my career, I originally worked in the area of manufacturing and design, and a few years back, when starting to get involved in autonomous vehicles, I went to an individual that I knew was experienced in the area.He told me that in many ways you can think of city streets to be much like a factory. But instead of moving parts around to different factory workstations, we’re moving people and packages around from place to place.” There are a lot of commonalities between what happens on the automated factory floor, and what happens with autonomous vehicles on city streets.

Today, we’re going to explore some of the commonalities and the differences and the role of technologies like Virtual reality and Artificial intelligence, in both autonomous vehicles, and in factories. We’re very fortunate to have someone with us that’s experienced in both these areas,Sofia Lewandowski. I met originally me Sofia when she worked the company HFM, where she was designing autonomous vehicles and making them better suited for the disabled, now she works for FactoryPal, where they’re looking to digitize the factory floor. With experience in both these areas, she is the perfect person to help us explore these commonalities and differences. Today, in Part 1, we discuss her work with autonomous vehicles and in Part 2 we will follow her on her path at FactoryPal to optimization of factories.

Sofia, welcome to the Future Car Podcast.

Sofia Lewandowski: Hello, Edward. Thanks for having me.

Ed Bernardon: You’ve studied economics, you have degrees in transportation, interior design, interaction, and user experience design. And you apply this, originally at HFM, to helping people with disabilities gain better access to mobility with autonomous vehicles. What inspired you to go in that direction?

Sofia Lewandowski: In that time, as I had to start with my master’s thesis, in Detroit, actually, I was looking for a unique topic but I already knew that I wanted to work on autonomous vehicles. I wondered what are they good for? What problem will they solve? Will they have a positive impact on our society? The answer for me was that AVs will enable people to do something they weren’t able to do before: basically, barrier-free traveling, access to transportation. In the US, at one of the Unreal Engine meetups, I met Ray Smith, a person in a wheelchair. And he was looking for some developers at this meetup. I saw him – I saw the chance, actually – and asked him for his opinion on my concept on my master’s thesis. We became friends after some time. He gave me regularly his feedback. And he inspired me to do more out of my thesis, and I saw the real need that autonomous transportation can solve many problems of people with mobility challenges – that’s why I was inspired by him and then started to look for my future, after my graduation, for the similar direction.

Ed Bernardon: So, your inspiration came from actually working with someone that could benefit from autonomous vehicle technology, and you brought virtual reality in to help you in the design process. When did you recognize or feel that virtual reality could play a part in designing and helping autonomous vehicles help people with disabilities?

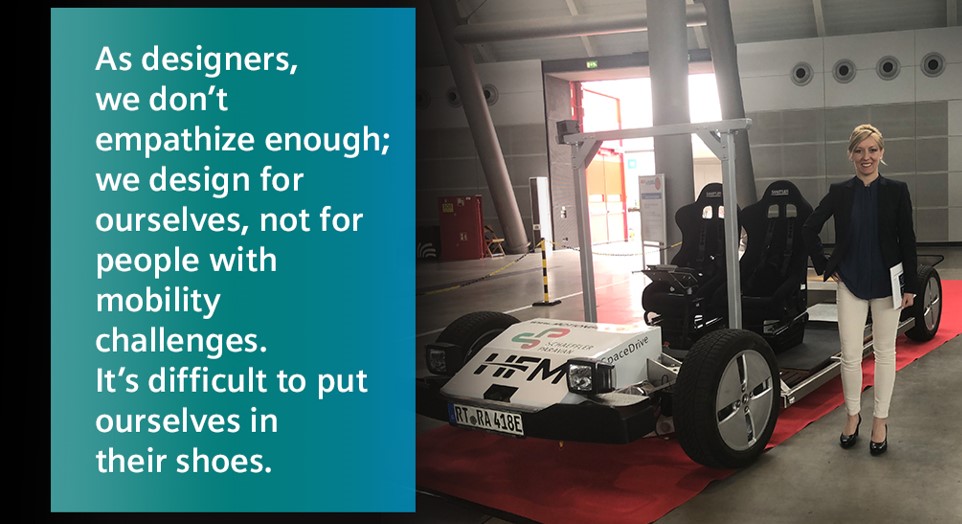

Sofia Lewandowski: As I started working on AV interior concepts, still during my university time at that time, for disabled people and tested them with users, I realized, we as designers, we don’t empathize enough; we design, basically, for ourselves and not for people with mobility challenges or for any other users. It’s really difficult to put ourselves in their shoes. I showed my users from a rehabilitation center – basically, people with mobility challenges – my interior concepts and sketches first, then I also showed them my ideas as 3D models. I figured out that the designs were unsatisfying for them. They always criticize something on my packages because I couldn’t understand exactly what they feel and what they need. So, I designed, for example, handles for them to lift themselves in the vehicle and transform themselves to the comfortable chair, to the comfortable seats in the car. But there was something that couldn’t work for them because they just don’t have enough power in their hands. So, I thought VR could give, actually, those people an opportunity to virtually build the custom interiors that would help them to slide from their wheelchair to a seat, they could test the proximity of objects, place remote controls around them how they wish it to be, and really try out things, put them around in the car, and create their own package they really need that I cannot create for them because I just don’t know what really is the need of them. And every person with a mobility challenge really have completely different challenges, let’s say. They have wheelchairs, electric wheelchairs, big wheelchairs, they need more space. Some of them, they have manual wheelchairs, and they also have other needs. Some of them don’t have hands and maybe need some supportive tools in the car. So, basically, I created for them an environment to be creative and support them. So, I didn’t say, “You are the designer to design now.” But I supported them by creating this virtual environment to create their space, I didn’t create a product for them but I created an environment to create.

Ed Bernardon: So, every designer or engineer has the challenge of having empathy with their customer, for the person that they’re designing the product for. It sounds like what you did is you flip things a bit, and you actually made your customer the designer.

Sofia Lewandowski: Right. I enabled them to actually be creative and put things around as they wanted, as they need it, and not just giving them a finished product that actually doesn’t work for them.

Ed Bernardon: And virtual reality obviously played a big role in this so they could see that environment before it actually existed, in a way?

Sofia Lewandowski: Right. So, we would avoid any additional effort. Let’s say, we wouldn’t need to build any clay models, any physical prototypes to test. Virtual reality feels real – so, you are in there, you test the proximity, you can grab things, you can really see how big is the environment. I think it’s very helpful and it saves a lot of effort, time to test before the production, before the first prototypes.

Ed Bernardon: Now, when we first met you were working for a company called HFM. What does HFM stand for?

Sofia Lewandowski: HFM is a German name: Hanseatische Fahrzeug Manufaktur.

Ed Bernardon: Now you know why I didn’t try and pronounce it.

Sofia Lewandowski: That’s why there’s a great variation.

Ed Bernardon: Can you translate? What does that stand for? HFM?

Sofia Lewandowski: Hanseatische Fahrzeug Manufaktur. So, it’s a car manufacturing or vehicle manufacturing company, based in Holm, one of the cities in Germany.

Ed Bernardon: What’s the goal of HFM?

Sofia Lewandowski: HFM actually creates or created a modular vehicle platform called Motionboard with integrated Steer-by-Wire and open interfaces to integrate any components. On top of the Motionboard, any kind of cabins could be placed. Integrated Steer-by-Wire from Schaeffler Paravan enables any kind of inputs to steer the vehicle, physical inputs to steer the vehicle can be sent by the conventional steering wheel, joystick, head movements, anything would be possible. So, basically, you can see this as a platform with the cabin on top. This platform is not just electric, modular, and connected, but it’s also accessible. So, this is something where we discuss with our customers if they wish the platform to be accessible, it can be accessible because we can integrate, or the company can integrate any components to the platform. It’s completely self-created, even the vehicle control unit has self-written software. So, the company can basically integrate anything that customer wishes to have in the vehicle.

Ed Bernardon: Now, is this primarily an autonomous vehicle, or can it be both?

Sofia Lewandowski: It can be both. The platform can be steered by wire, and steering by wire means that we could have physical inputs. As I said, with the conventional steering wheel, it’s possible to steer the vehicle with joystick, with any kinds of inputs, there are a lot of different ideas what can be used, like the user can, for example, blow in the tube, and in this way could apply brakes and accelerate, or turn the head to the right and left and the sensors would catch the head movement and also steer to the right or to the left, which would be good too for disabled people or people with mobility challenges. But it also can be autonomous or highly automated, we say highly automated by integrating the sensors in the autonomous software. So, the company doesn’t create autonomous software for that, for example, there was another company IBO but it can be any other companies as well, to create the software. So, basically, we integrate components, and it can be highly automated but it also can be manually steered.

Ed Bernardon: So, what was your role at HFM in the design area?

Sofia Lewandowski: As I started at HFM, I created AV interiors because that was my degree for my bachelor’s. I was working on concepts for interior, cabins that go on top, these four different use cases, different users, different customers. In the next step, I created web pages brochures for the company, posters for exhibitions, and kind of stopped doing too much design work but it was kind of everything in the company – so, outreach, I started traveling to conferences; I gave talks at the universities meetups, summits; I reached out to state representatives, especially in the US; I joined delegation trips to China, pitched company to investors.

Ed Bernardon: So, there’s the Motionboard which is underneath, and that has everything that drives the vehicle, many of the control systems related to that, you could plug in through your, as you were calling it, drive-by-wire to do the steering, the starting, the stopping whatever it might be. But then you have this cabin that goes on the top. Let’s say it’s an autonomous vehicle, you’re not so worried anymore about the actual driver but you can now start to create whatever environment you want in this cabin. Can you tell us a little bit about when someone looks to get one of these vehicles, what do they look for in an autonomous vehicle when it comes to the interior? What’s the variety, the different types of things that you encountered in the design of these interiors?

Sofia Lewandowski: So, there were completely different use cases that we looked at. We had different customers, or potential customers also, who had different ideas of how to use these cabins, how to use these autonomous or highly automated vehicles. We always started with the use cases: what is the goal of the trip? What is the route that will be covered? Who will be the user? And what will they try to accomplish, these users?

Ed Bernardon: What were some of the unique use cases that came about?

Sofia Lewandowski: We were working with, it was actually a city project that we conceptualized one interior, where the seniors were transported from senior apartment buildings to downtown area and to grocery shops, and were brought back. So, basically, the routine wasn’t a long one, just a couple of kilometers, a couple of miles. In this use case, we knew that the seniors probably will have a walking aid, they would need space for a dog, place for grocery bags, guiding rails would be necessary to integrate in the vehicle, big letters on displays, analog and simplified design. So, this is something that we had to consider by designing this concept for this project.

Ed Bernardon: Any other examples?

Sofia Lewandowski: If I think about another concept where we worked with a university, also, the idea was to transport students on the campus. The shuttle would just run around the campus, and on this shuttle, there would be four students, let’s say with software background, and they would code something on the vehicle, for autonomous vehicle, and the supervisor would sit on the bench behind them. So, basically, for this interior, we would need a table and four chairs with a socket wireless charging for their phones because we are talking here about young generation; they always have their phones with them. This is a completely different interior now compared to the interior for the seniors who would go for shopping to the downtown area.

Ed Bernardon: It’s interesting when you think about design, if you have unlimited capability to go anywhere with a design, you would think, “Oh, that makes it a lot easier.” But that can also make it a lot harder because now you have to figure out in what direction to go and what you need to do. So for instance, here, you said, the seniors, they needed room for their grocery bags, the students wanted a table where they could sit around, talk, and collaborate, how do you go about figuring out, in an efficient way, what you really need in that interior? Do they always know what they want or do you have to help them figure it out?

Sofia Lewandowski: We also figured out that the users don’t always know what they want. There are two use cases, if you talk to the customer, they have a general idea of who should be on board and what route should be actually covered. But what the users and the end users would need, that would be interesting to figure out with the users themselves, not with the customer. So, that’s where we had to actually ideate first, what these users could need, and then talk to the users. Let’s say, in the university, there could be the students we will talk to figure out what do they usually have with them? What do they need for coding anything on board of such a shuttle? What else would they want to see in the vehicle? So, it’s basically always talking to the customer first and getting the requirements, because they always know what basic requirements they would need, and then talking to the user and figuring out what the user actually needs on this shuttle.

Ed Bernardon: It’s a lot different than buying a car where you say, “I want this option or that option.” It’s more figuring out what a user needs, rather than necessarily what they say they want. There’s a difference between those two, it seems like. Now, when you do this for someone with disabilities, how does this design process change?

Sofia Lewandowski: When disabled are involved, we still start from the beginning, we need to figure out what is the use case? Where does the person go? And what will this person try to accomplish? Will it be always a business trip on the specific route? Will it be a pleasure trip? Or will they also be just shopping somewhere downtown? So, the technology would enable the access to the vehicle that HFM has. For example, automatically-deploying-ramp would help to get them on board; air suspension is also available in the platform, it would lower down the vehicle to also enable these people to get on board easily; rails would be necessary, for example, special interior package with enough space to maneuver around in the vehicle; if they are in a wheelchair, then we need to think what wheelchairs will be on board, electric big ones, or manual ones, which are smaller ones; also, seat belts to fix the wheelchair automatically – it would all need to be considered in this cases. And I’m here only talking actually about people with mobility challenges but there are many more disabilities, for example, blind people can be on board, people with other challenges. So, we always need to know who will be the target group

Ed Bernardon: Every one of these customers may have somewhat unique characteristics that you’re going to have to work with, maybe it’s the level of disability or the type. It seems that that’s where virtual reality comes in, to help you come up with the solution that they truly need. So, can you tell us a little bit some specific examples of how you use virtual reality in these kinds of situations?

Sofia Lewandowski: Basically, I was working at the university, first, on my thesis, and there I used VR really to let people create their environments. At HFM, VR enabled us to demonstrate different AV concepts at exhibitions, conferences, summits of how different interiors would look like. Disabled people could look inside and judge the experience by commenting, and suggesting any improvements.

Ed Bernardon: Would you start with a specific design and say, “Hey, let’s start here.” Or is it more of a blank sheet where they might pick things from menus and say, “Hey, put a chair over here, and a screen over there.” How do you start?

Sofia Lewandowski: I think it would be very challenging to put a person in a really empty room in virtual reality and give them the opportunity to use all the possible furniture pieces because then you start from scratch and not everyone feels comfortable to jump into the role of a designer. That’s why it’s good to have some samples. So, in virtual reality represented, for example, three different samples of how this interior might look like for disabled people, and then there was an opportunity to actually play around and change the places of some of the objects. Let’s say, they would remove the chair from one position to another, they would maybe adjust the height of the seat, and so on. So, basically, starting from samples from existing examples in VR, and then kind of redesigning whatever we already were thinking about.

Ed Bernardon: Is it more things like we could lift the level of the seat that they’re trying to move into? Is it that, in addition, say, to, “Oh, I would like to place this hand strap in this location.” Or, “I’d like to have a screen over there.” Or, “Oh, I’d prefer a leather interior versus a cloth one.” What’s the range of choices? It seemed like there could be so many here.

Sofia Lewandowski: The leather and all the other options that you can have in a conventional vehicle, we didn’t really demonstrate, it was more about placement of objects. let’s say, recreating the package so that it’s convenient for the person in a wheelchair. And also changing — let’s say, they could just move objects and adjust the seat height so that we know what is more convenient to them. It was not that much about little details, this is something that we would already discuss with, let’s say, customers and end-users but not on these exhibitions where it’s all about demonstrating that it’s possible to recreate and really create a custom experience in the vehicle.

Ed Bernardon: You create it virtually, you do it with virtual reality, but then ultimately, you create the actual hardware itself, the actual vehicle. I would imagine there isn’t always a perfect match, there are going to be some differences. Have your customers ever noticed any particular differences? Do the types of differences stay the same? Or how close has virtual reality actually get to what you ultimately create in hardware?

Sofia Lewandowski: So, if you create a 3D object, we used to work also with a seat company who created the seats and we place basically the same seats in the car. As we developed further, we just took the objects that the customer wanted to have and asked the suppliers if they can give us a 3D model, or try to recreate it ourselves so that it’s close to the reality. And then of course, as let’s say, we didn’t that time produce the seats and all the other components, of course, we outsourced all that. And before integrating in the vehicle, we showed, actually, the components that we ordered to the customer if that would be actually what the customer imagines it to be.

Ed Bernardon: Sofia, thank you so much for speaking with me on the future car podcast. That concludes Part 1 of our discussion on design for mobility. In two weeks, we will get together again and talk about Sofia’s work on the future of factory design. We will explore some of the similarities and differences and the role of technologies like VR and AI, in both autonomous vehicles and on the factory floor.

And of course as always a big “Thank you,” to all our listeners, so until next time, I’m Ed Bernardon, and this has been the Future Car Podcast.