Zoox’s Journey to Safety with Mark R. Rosekind – Part 1

Will autonomous cars be safe? Challenges posed by different city terrains and weather conditions.

What capabilities would a vehicle that can successfully circumnavigate the globe need to possess? With autonomous vehicles, the goal is to get to a point when they can give us a “boring” or uneventful ride.

And you may be thinking, “Well, that’s not exciting at all!”

But, it’s safe and trustworthy enough for you as a rider to shift your focus from the fact that there is no driver. After all, it’s only after you feel safe that you can fully relax and enjoy the ride as well as all the amenities that come with the vehicle.

AV companies are tackling this challenge head-on by borrowing safety approaches from the aviation industry as well as innovating new strategies.

In this episode, the first part out of two, Ed Bernardon interviews Mark R. Rosekind, Chief Safety Innovation Officer at Zoox, Inc. He’ll help understand the challenges of building an autonomous electric vehicle and the progress they’ve made so far. He’ll also share with us the steps that the automotive industry can take to increase people’s safety on the road.

Some Questions I Ask:

- What do you consider while designing your vehicle? (09:48)

- How do you create “a journey to enjoy”? (10:54)

- How do you know that you’re safe enough? (19:48)

- What does “a safe system approach” mean? (22:12)

- Are you doing anything special to enhance communication with first responders in case of an accident? (29:24)

What You’ll Learn in this Episode:

- The history of Zoox (02:30)

- The difference between proactive and reactive safety (13:29)

- The difference between how the aviation and automotive industries approach safety (15:45)

- How the Zoox vehicle will communicate with people around it (23:26)

- What it takes to gain people’s trust (33:00)

Connect with Mark R. Rosekind:

Connect with Ed Bernardon:

- Future Car: Driving a Lifestyle Revolution

- Motorsports is speeding the way to safer urban mobility

- Siemens Digital Industries Software

Ed Bernardon: Mark, one question I have is Zoox is a really interesting name; where did that come from?

Mark Rosekind: Off the coast of Australia, these are microorganisms that are symbiotic to the coral reefs that you find. That’s where Zoox came from; to be symbiotic with ecosystems. And it really is at the heart of what Zoox does.

Ed Bernardon: When I look at the name, and of course, you’re Chief Safety Officer, it’s “Zoo” with an X on the end. Does anyone ever think like you’re maybe in animal safety or in the zoo business when they meet you if they’re not from the autonomous car world?

Mark Rosekind: Well, you know what’s interesting? There is another company that sounds similar to ours, but it’s a little more in the relationship end of the kind of apps that you can get. So, we get more confused with that than a zoo. To me, I think Zoox is pretty straightforward. You just spelled it. It’s amazing how people end up pronouncing those four letters.

Ed Bernardon: Zoo-ex, Zoox, who knows, right? Well, maybe you have a career in animal safety if this doesn’t work out someday.

- Intro music

Ed Bernardon: Not long ago, the idea of opening an app on your phone to order a ride from a stranger created more than a few skeptics, but rideshare services have quickly won over millions of us who continue to rely on them daily. So what’s next?

Our guest today is the Chief Safety Innovation Officer for Zoox that is creating the next leap for the rideshare industry, a fully autonomous, driverless vehicle to provide mobility-as-a-service in a way that’s never been seen before.

Welcome to the Future Car podcast I’m your host Ed Bernardon and when it comes to autonomous cars, the big question is: Will they be safe? Today’s guest, Mark Rosekind, has been on all sides of safety. He was on the government side with the National Transportation Safety Board and now he’s focusing on safety on the commercial side at Zoox. Mark explains how Zoox is striving for sustainability, the major challenges they anticipate with different city terrains and weather conditions, and how passenger and pedestrian safety is their top goal.

He is just the person to give us a true perspective on autonomous vehicle safety and he may even teach us a card trick or two.

Ed Bernardon: Mark, welcome to the Future Car podcast.

Mark Rosekind: Ed, a pleasure to be here. Looking forward to talking to you.

Ed Bernardon: Well, let’s start off and maybe just tell us a little bit what Zoox is all about. There’s a lot of autonomous car companies out there, they don’t all have the exact same approach to autonomy. Tell us a little bit about the Zoox story.

Mark Rosekind: Zoox, from the very beginning of its creation in 2014, has taken a fairly unique approach in wanting to, basically, integrate the ecosystem of mobility. And when you think about it – this moment of transformation that’s in front of us – we can really enhance safety, mobility, and sustainability in our society, and Zoox wanted to do all three of those. And the company really believes that we need an integrated system to pull that off. And so the unique part was, we were doing the full stack: build a vehicle from the ground up specifically for autonomy; do the AI and all the computer pieces to make that operate; and three, actually provide the service as well. That integrated system, we think, is going to be the best way to deliver this service into the real world. And we’ve seen that work in things like the iPhone, and that is nothing compared to the complexity of transportation where lives are on the line.

Ed Bernardon: If you are just going to make autonomous vehicles to sell. In some ways, that’s a lot easier than what you just described because not only do you have to create a vehicle, but now you have to worry about charging, maintenance, infrastructure, buildings, and the places where you’re going to store the vehicles. So, a lot of moving pieces to doing the whole Mobility-as-a-Service with autonomous cars.

Mark Rosekind: Yes, and thanks for raising that because it just adds a little more depth. Zoox is all-electric, it’s designed for sharing, and specifically in congested urban settings. So, that’s where we’re hoping to, again, increase the safety, move people around – where you don’t have to own a car, you could share one of the Zoox vehicles. And one of the really cool unique things about Zoox is its vehicles are also bi-directional – there’s no front or back. So, when you think about, again, a dynamic, complex, and congested inner-city – we won’t ever have to make u-turns or three-point turns, etc. It’s built for operating in that congested urban setting. And to your point, yeah, it’s harder because you’re not just putting something into an existing vehicle; you’re talking about building from the ground up to answer and deal with this problem of all the congestion, the safety, and the problems of moving people in big cities.

Ed Bernardon: So, when you build a company to do this, you have to look for a wide variety of people then. In other words, it’s not just engineers that are going to engineer the car or software, but you have to have people that know how to maintain a fleet of vehicles.

Mark Rosekind: Yes. And again, your previous question went to that, which is, it’s not just about the engineering of the vehicle. And in fact, I like to point out, I think the big challenges right now are the actual deployment; rubber meets the road in cities, how you’re going to do that? So, as you were just asking previously, it’s like, what about the grid? We’re all-electric. How do you make sure that the city is prepared for that? You need more of the engineers just to figure out about the movement within the city, and when there are pop-up construction zones, and all the dynamic aspects of the other road users that are there that you have to interact with – much more complex and dynamic in a congested urban setting than when you’ve got sprawled out country settings, for example. So, yeah, a lot harder. I always bring up: more complex, more dynamic makes it harder, but it’s also where we’ve got bigger problems to solve.

Ed Bernardon: And I would also think that not every customer is the same. So, you have cars in San Francisco, you’ve got them in Las Vegas, you’ve got them in Seattle. Certainly, Las Vegas is a lot different than San Francisco or Seattle. And you’ve been in government, and you have to deal with the nature of the people that drive in those different cities, you have to deal with the government. There must be some big challenges when you’re trying to keep your customer happy.

Mark Rosekind: Yeah, and you’re pointing it out. Just think about all the cars that are available to people. Why? Because there are so many different interests and styles for what their use case is, for what makes them happy to drive, etc. So, to your point, it was so much individual difference there. And we need and want to hit that sweet spot where we can put a shared experience together that’s really going to solve congestion and all kinds of other problems that we see happening in our urban centers. I think Zoox is really striving to be that solution; to be as safe, and make sure we move people around in ways that we just don’t see right now. And being all-electric from the very beginning, we want to help make sure we sustain the planet as well. But thanks for pointing that out, because that’s a hard thing, given all the different individuals who are going to be asking for a ride.

Ed Bernardon: If you could point out – and those are your three cities: Seattle, Las Vegas, and San Francisco – what do you think are some of the unique characteristics in light of trying to deploy autonomous vehicles that’s different between those three cities?

Mark Rosekind: That’s really interesting because let’s just start with San Francisco and hills. The geography is so different. And we’ve got fog, and we’ve got some rain occasionally, but you’ve just got everything from the geography to the weather. And San Francisco, which has such an interesting dynamic of people and vehicles and other road users that are out and about. Las Vegas, the geography is different. Think of this strip and just how clear that is. And it has a very interesting pattern to it. It’s all built around the casinos, and big hotels, etc. And yet, it’s also interesting, because as soon as you start moving out, boy, it gets to be wide open. And Seattle, what a wonderful dynamic place that also has lots of rain, different geography. And so, as you’ve just pointed out, each city actually offers different things to learn and different things to offer for both, the geography, weather, and people of those different cities. And by the way, what you’ve also highlighted is there is no single solution. You actually have to be able to deliver a lot of different solutions to so many different people. And you do that by actually interacting with those different environments to figure out what they need and what you can deliver.

Ed Bernardon: If you had to pick the next city, not to say that you’re actually going to that city, but if you had to pick a next city that would give you some additional information that you hadn’t gotten from those three; what city would you pick, you think?

Mark Rosekind: Go East. And I think you’re looking at New York or DC. And then if you really want to go northeast, pick a place that’s going to give you the snow and ice and those kinds of things. And that’s what’s great is what you’re highlighting; you can control that operational design domain and decide what geography and weather pattern you’re going to actually be working in, and then expand as you start being able to deliver on the engineering that’s going to actually get you to snow and ice, for example. So, interesting question, because we’re all West right now. I think the next big challenge would be for us to go East. And I just gave you three examples: DC; New York; maybe Connecticut; even better, Vermont; or Massachusetts, where you’ve got snow and ice.

Ed Bernardon: We’ve got plenty of it here in Boston. I know May Mobility, which is a similar company to Zoox – they’re actually operating in Rhode Island. I would imagine, you think about snow and ice and all that in visibility, but there’s also the durability of the vehicles; having to put up with salt on the roads and things like that, like real car design types of things. Is that a key part of what you think about when you’re designing your vehicles? Or is that something you’re going to leave when “Hey, we’ll tackle that next when we go up North and East”?

Mark Rosekind: That’s such a good question because we’re designing for the full range. And so, for example, we’re talking about operating in a congested urban environment: 25 miles per hour, Las Vegas; there are some places that are 35 or 45 miles per hour around the city. But our vehicle is actually designed to go 75 miles per hour. And so it’s designed to go top speeds, it’s designed for different geographies, different weather patterns. And so it’s designed to go wherever it needs to be, and that includes, with all these different weather conditions, speed limits, and the kind of people – whatever it is they’re going to need, we want to be able to go there. So, we’re not leaving that for the future; we’re designing and testing the vehicle now for all of that.

Ed Bernardon: Your platform for mobility, designing it from the ground up, which opens up a lot of things for you to do. And one of the things I saw that you talk about is a journey to enjoy, maybe like a living room on wheels. How do you create a journey to enjoy? It sounds really, really good.

Mark Rosekind: Well, let’s start with, we get to design a vehicle from the ground up for you, the rider. The cars on the road today are mostly designed for a driver in the left front seat; we’ve got to put a steering wheel, we’ve got to put all the operating controls. In fact, there are even different crash criteria for the front versus the rear seat. So, what happens, with a clean slate, we get to say, “The rider is the priority, what do we create for them?” So, it begins with the fact that we’re carriage seating. It’s not rows like this, it’s like carriage seating. Talking about going old school – I mean, it’s a carriage for you, the consumer.

Ed Bernardon: Carriage seating is face to face?

Mark Rosekind: Yeah, two people looking at the other two people. And so it’s a very social environment, it’s a nice open environment. You’re not worried about your knees. I’ve been in our vehicle that’s been built and it’s in crash testing already, etc. I’m 6’4’’ and I’ve been in with other folks about my height, and knees don’t touch, there’s a lot of room – so it’s very spacious and open. And yet each individual seat also has controls over their music, the air conditioning, and the other things that make it comfortable. And we’re designing for sharing – so, you could go in on your own and be the only person in there. But you could also be in there with your family or your friends, or three other strangers. So, it can be very social, or you could just be there working on your own stuff, bringing your pad in there, and doing whatever it is you want.

Ed Bernardon: Have different forms of entertainment. I suppose you’re still going to have all the entertainment that’s on your phone. Is it all really based on that? Or is there going to be some built-in forms of entertainment or other types of things that you might have in a living room, say?

Mark Rosekind: So, right now, you’ll bring it with you. It’ll be your phone, your tablet, or pad, iPad, whatever it is that you’re using. But I think those are the kinds of things that we’ll see how people’s interests and needs get us to the next generation. Because I don’t have to tell you, there’s just a huge opportunity for bringing in all kinds of entertainment and other uses into that. If you’re no longer having to worry about the driving task, then all that time in that vehicle is now yours again. Whether that’s entertainment, or work, or sleep, or whatever it is you want, it just opens up time for you again.

Ed Bernardon: Let’s move on to safety because I know that’s a topic you really want to cover. And I think one of the interesting things that you’ve mentioned is this whole idea of proactive safety. I’ve heard you say that the aerospace industry has been proactive, but the automotive industry has been more reactive. So, what exactly is that? Maybe you can give some examples from the aerospace industry? And what’s the difference between proactive and reactive safety?

Mark Rosekind: So, let’s just start with auto and reactive for most of 100 years, and that is, crashes are going to happen — after the fact, how do we figure out to make things safer? And so that, unfortunately, means we’re just acknowledging crashes are going to happen and how do we help more people survive them? Proactive is when we’re thinking how do we do safety efforts ahead of time that prevent those collisions, injuries, fatalities from happening in the first place? And so, I like to point out, our prevent and protect, basically, says the ultimate safety is preventing that crash from happening in the first place. And so new technology that allows you to have automatic emergency braking so you don’t crash into things. You’re planning so that you actually don’t get close to where there’s something that’s going to be a risk for you, that it automatically adjusts your speed for whatever the weather is, etc. So, those are the kind of proactive things that you can do that help you deal with situations that prevent those crashes or injuries or fatalities from happening in the first place. And aviation has just done a great job. I mean, they had, a couple of decades ago, some horrible crashes with too many people losing their lives. And they said, “What are we going to do to try and make this better?” And so whether it was in training or procedures or technology, they did whatever they can. And I point out, commercial aviation went 12 years in the United States with no single fatality. Twelve years with zero fatalities. We’re in crisis on the road. But if we could get to that level of safety, it would be superb. Right now, 95% of all fatalities and transportation happen on our roadways. How do we use those lessons learned, apply them to the roads and start saving those lives?

Ed Bernardon: Do you think that the aerospace industry focuses more on safety? Or they just focus on it in a different way that the automotive industry hasn’t learned yet or just hasn’t applied?

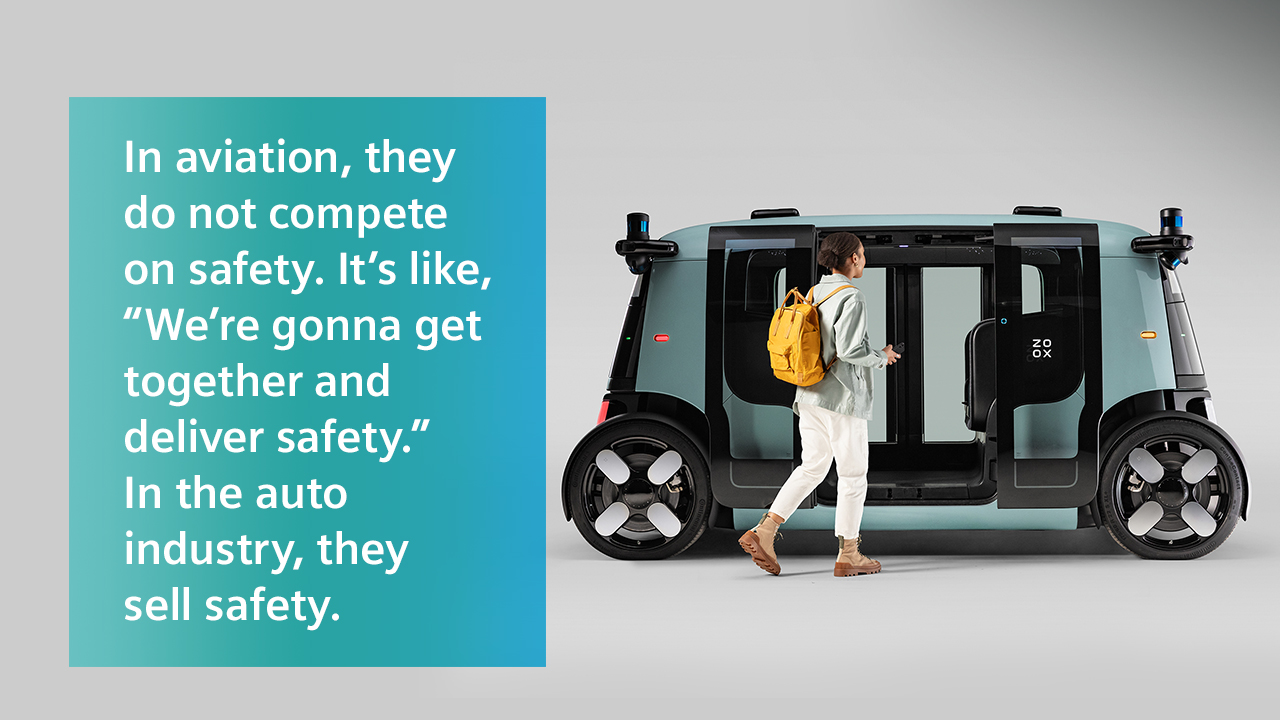

Mark Rosekind: Great question, because I’ll tell you the answer, which is that in aviation, they do not compete on safety. It’s not a competitive issue – it’s like, “We’re gonna get together and deliver safety.” In the auto industry, they sell safety, right?

Ed Bernardon: Yeah, certainly, Volvo.

Mark Rosekind: And all the other cars look at this system. And again, I ran NHTSA, which does the New Car Assessment Program, NCAP. Those are stars for cars that you see right there on the window of the vehicle. So, you’re literally, “Is it a five-star or four-star?” You would never get on an airplane and say, “Gee, where are the stars next to the cockpit, so I can see if it’s a five-star cockpit or four?” You don’t compete. You want everyone to be five-star. And so, I think that’s one of the basic things. And it’s not that the auto industry doesn’t collaborate on things. But I think sometimes the going in is always trying to — And so as administrator when I was at NHTSA, one of the things we talked a lot about is how do you democratize safety? There really should be one level for everybody. And so whether that’s making pricey safety options – automatic emergency braking – available for everyone, or one of the latest issues you see is, guess what? Crash dummies should actually represent our population in our society, not just 95% male or 50% male. We really should have one level of safety for everyone. Whatever gender you are and wherever you’re sitting in the vehicle, we need to get there. And I think there’s clearly room in the auto industry to emulate some of the things that have happened in aviation.

Ed Bernardon: How do you get an industry – like you said, they’re competing, they love their five stars of safety, and the other guy only got four or three; how do you get them to say, “We’re all gonna work together”? Is that the role of government somehow to provide incentives? How do you do that?

Mark Rosekind: Again, what a great question. So, having been in a lot of different environments – board member at NTSB, and administrator at NHTSA, and a scientist at NASA – I’ve had a chance to see the safety system from a lot of different angles. And what your question brings out is there is no one group responsible for safety in the auto industry; it’s all these groups playing their role. And what you just identified is, in fact, one of the critical roles for government, for NHTSA, for the Department of Transportation to be able to step in and say, “Look, these are the big objectives. Here are some specific things we expect everyone to do.” Sometimes that’s regulation, sometimes that’s another policy, sometimes it’s something else. And then how do we reinforce and incentivize people to do those things well? Because that brings safety to everybody. And so if you don’t have every sort of player, every stakeholder fully engaged, then you’re going to have gaps. And so to your point, some of those changes have to come from the government. But you know what? Industry does that, too; they do best practices; they don’t wait for the government to say, “Regulate us. We’re going to do this.” And I bring this example up all the time as administrator, we challenge the industry to make automatic emergency braking standard on all vehicles across their fleets by 2022. I mean, this was in 2015, it would have beat regulation by four or five years if they could do that. And 20 of them signed up, accounting for 99% of all the new cars manufactured, and they’re pretty much there – I mean, we’re in 2022. So, that’s the democratized safety. Government didn’t have to regulate, but it gave the challenge and the industry stepped up. Now, guess what? You could do it faster, you could do it better if you want. But at least everyone is going to get that democratized safety, everyone’s going to get that level of automatic emergency braking, that pretty much equals the playing field for everyone.

Ed Bernardon: Safety is an interesting thing in the sense that when is safe, safe enough? – “Well, that could be a little safer. Is it 99.99 or 99.99999?” And the cost goes up as you try and grab another 9, I would think, behind that decimal point. How safe is safe enough? How do you know that you’re safe enough?

Mark Rosekind: Well, it’s not the question of the hour, it’s the question of the last 100 years. So, two things quickly, and then we can go further if you want. One thing I point out is, everyone asked that question related to autonomous vehicles. And I point out, we’ve actually not answered that for the current road safety system. 30,680 people lost their lives in 2020 – 100 people a day. Is that safe enough? No. So, we haven’t defined that, how safe is safe enough, for the last 100 years. So, to think that somehow we’ve got the right metrics, or methods, or even data to say, “We know how to define that now for this new technology,” is kind of naive on our part. So, I think it’s a very healthy discussion. But I think it’s also bringing up stuff that we haven’t answered for 100 years. What makes you think that ask me that now and we’re going to have an answer? People are struggling to figure out what that means. Now, there are some things which I’m so pleased to see, the Secretary at the Department of Transportation just came out with a new national road safety strategy. And for, really, the very first time, DOT is saying, “Our objective, zero lives lost.” That’s big. And if you think about it, that’s the way-out objective.

Ed Bernardon: How far out do you think that is?

Mark Rosekind: Well, there’s a study. Before I left NHTSA, we helped get a group of “Road to Zero Coalition” together. They’re now 1,600 organizations that worked with RAN, and they came out with a report that answered your question, which is, in 30 years, you could get to zero with three things: emphasize, double-down on what works; two, further implement the safe system approach; and three, advance new technology. Those three things were identified and discussed. And if you really went after all of those, in 30 years, you could get to zero.

Ed Bernardon: We could probably talk about this for the entire hour. And we’re definitely going to get into the technology part, your third one. But just real quick: safe system approach. What does that mean, safe system approach?

Mark Rosekind: It’s so interesting because people say it’s the hot new thing. It’s not new. This came from Sweden, it’s a wonderful work they’ve done, that looks at the system, human choices and errors contribute — and people are screaming about this statistic, but 94% of the last cause in a crash is something that humans chose or an error they made. And the safe system basically acknowledges, “Well, errors happen.” So, what can we do? Designing the roadway system or speeds that help us control those kind of choices and errors so they don’t end up in somebody losing their life. So, that’s the more system approach that gets to road design. I mean, the classic example of roundabouts that control speed, for example, cameras that maintain that. And in Sweden, using the safe system approach, they’ve cut their fatalities down by 50%. So, I mean, we know it works, and it’s now being more emphasized in the DOT proposal. And for the last five-plus years or so, maybe 10, in the United States.

Ed Bernardon: There’s a lot of different aspects to safety; there’s safety inside the vehicle, there’s safety of the people that are around the vehicle. Thinking a little bit about around the vehicle; conventionally or traditionally, non-autonomous, there’s a lot of communication, eye contact, or whatever there might be, between the driver and the pedestrians. Here in Boston, there’s this rule. If you’re about to enter a roundabout, don’t look at anyone in the roundabout. Because that means if you make eye contact, they have the right away; if you don’t look at them, then they’ll stop for you. And there are different rules of the road on how you do that. So, what is Zoox doing when it comes to trying to communicate with the people that are going to be around one of your vehicles?

Mark Rosekind: So, this is a really, really important question, because you and I are used to that social contact, the interaction where the eyes connect, your body’s looking at it, or literally, you’re waving. You’ve got communication methods that we employ. So, at Zoox, we’re using light and sound. And so we have a couple of really cool things that our folks are working on to use sounds – to let you know, not just that we’re there, but what our intent is – as well as lights, and the combination of those two, being able to really communicate our intent. Because the two things are; one, I see you; and two, here’s our intent: I see you and I’m holding; I see you and I’m slowing down. So, we’re using light and sound to communicate those things. And your question earlier gets to the point; there are so many individual differences, you’ve got to figure out what are those communication signals going to be that actually mean the same thing to as many diverse people as you can?

Ed Bernardon: Well, and I was actually going to just ask you that. We all know when that turn signal is flashing on the left side of the car, it’s going to turn left. What is the sound? And even if you figure out what the sound is, or visual signals, how do you get everybody to use the same thing? Or is that already happening?

Mark Rosekind: It’s not. And that’s a great point, which is, all companies that want to do fully autonomous kinds of driving, have to figure this out. And what you’re highlighting is, there are some areas where either government needs to be involved or the industry needs to establish best practices so there are consistent messages. So, when somebody turns their left signal on, it doesn’t mean they’re turning right or going straight. I mean, there are these conventions we know for sure now. In this new world, what are those new conventions going to be? And having those consistent for all of us. I mean, we’re all pedestrians at some point. And so if we need to know what those signs and signals and messages are, how do we make sure they’re consistent? So, we all know what they mean.

Ed Bernardon: So, I’m about to step onto the street. You call it a Zoox? What do you call it? Does it have a name?

Mark Rosekind: It does, but we’re not really talking about that yet. But we do call it a vehicle because it’s not really a car – so, the Zoox vehicle.

Ed Bernardon: All right, a vehicle. We’ll call it the vehicle. The Zoox vehicle is approaching. How’s it going to communicate to me; one, that it sees me; and two, is, “Hey, don’t worry, I’m putting my brakes on, go ahead and cross.” How exactly does it do that?

Mark Rosekind: So, one of the things that we have talked about publicly is, we actually have a speaker array that is beamforming. So, it literally can send a signal. You’re going to step off the right side curb, I can send you a signal, and the people crossing and doing something on the left won’t even hear it, or won’t even recognize it. So, remember what we talked about. The first thing is to get your attention, so you know I see you. And then the second is to communicate whatever the intent is. And so that audio signal could go right to you to say, “I’m here. I see you’re there.” And then the next signal, which could be an audio signal, will let you know what we’re doing. And so we’re testing those signals to figure out which are the ones that communicate to you: “We’re stopping,” versus “You have a red, you need to stop.” We’re still not going to go if you were to cross, but to try and get your attention to get your head up from the phone, notice it’s a red, you’re supposed to stand there. So, again, that first thing is the signal that gets your attention to make sure we’ve got that contact so we can send you the next signal. But just so you know, to be clear, what those signals are, to make sure that absolutely you know the intent – those are still being developed. Nobody’s got a set of those that are automatic or well-known, people are still trying to figure that stuff out.

Ed Bernardon: Yes, that common language we were talking about before. Will it be a signal or will it be a speaker that’s projecting a spoken word like, “I see you.” Or is it some sort of a beep sequence? What do you think?

Mark Rosekind: Yes. So, one of the things is, I’m telling you a bit about the beamforming because when you hit the horn, that gets everybody’s attention. It’s not focused in any way. So, the beamforming allows us to direct the message. But you’ve got it, which is, should that be a word? Should that be a series of beeps? Should that be ongoing? That’s the communication language that’s being developed. And as you said, would it be great if it becomes a common language, rather than every company’s got their own version of it?

Ed Bernardon: Well, I would imagine that when cars were first introduced onto the streets of New York or wherever it might be, there probably wasn’t a common language then either. It’s something that evolved over time. One would hope that that could happen a lot more quickly than it probably happened 100 years ago when cars were introduced.

Mark Rosekind: Absolutely. And there are Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards that get to the “telltales”, which are the signals and other kinds of things, brake lights, and how those work to make sure that there are standardized ways the vehicle communicates with the people around it. So, some of that is actually built into the regulations.

Ed Bernardon: Another form of communication is, should there be some sort of an accident and there’s a first responder coming in or a team coming in; with autonomous vehicles, you’re losing a level of an ability to communicate, because it’s not the person’s car that they own. Are you doing anything special to help with that?

Mark Rosekind: So, this is personal for me, because I come from a law enforcement family. And so Zoox, in particular, has a very high priority on first responders. The first thing that comes up always from first responders is how do I even know what your vehicle is doing? Is it stopped? Is it gonna move? And then we get to the joke scenarios of, “Who do I give the citation to?” There’s nobody in the vehicle, there’s no driver. “License and registration, please. Where do I find them?” And then, of course, the more serious things that if something happens, and they have to actually get in for a medical emergency or something else, how do they do that? And so we’ve had a lot of interaction with the first responder community, which is usually law enforcement, fire, and EMT. And I always point out, it doesn’t matter what city you go to, they’re core of the city. The politicians come and go, and other things change, but those are core. And so that’s another place where a lot of companies — And again, for us, it’s a priority, it’s personal for me, but we’re having a lot of interactions with folks to figure out what kind of educational material do we have to create? What kinds of guides do you need? A lot of people focus on the electric part – what part of the battery do you have to stay away from? Cut here, cut there. But as we were just talking, there are all these other issues, about “If I’m going to pull this vehicle over, how do I know what even sees me? Or it’s going to do what I need to do? And if it pulls over? Who do I talk to when there’s nobody in the vehicle?”

Ed Bernardon: Yeah, who do you talk to? What do you train them?

Mark Rosekind: In the Zoox case, we have microphones and speakers. And so because we have a tele-guidance system, a human in another center somewhere, monitoring the vehicles in our system, we would know if that vehicle is pulling over and could literally talk directly to an officer or firefighter or somebody who is approaching the vehicle. And by the way, it also can make it easier. Rather than look for insurance or other kinds of things in the vehicle, we literally could say, “What do you want? I’ll email that to you. I’ll text you whatever you need.” And then you even have it in digital form. So, we’re talking about evolution in a bunch of those areas that could be good for everybody as well.

Ed Bernardon: I think you’ve really hit on something that’s really important that would give people more comfort of being in an autonomous vehicle, which is, in the end, there is a human back there somewhere that is going to get alerted and take care of you, should it be beyond what the systems can take care of on their own.

Mark Rosekind: Absolutely. Trust is a huge thing here. Just trust in these systems, not just how safe, but they’re going to get you where you want, etc. And so at Zoox, the vehicle is going to have the intelligence, the AI, to operate wherever it needs, but there is a human in the loop. And we consider it sort of like an extra sensor to help with situational awareness. And so if you have just a question in the vehicle, or there’s a medical emergency, somebody else hits the vehicle, or anything happens – there’s always a human that’s in the loop, that is in communication, that can help with anything that occurs. Now, they’re not there ever-present, it’s more like if they’re needed, we can pick up things where they need to get involved, or if you ever want to make a call and say, “I need to talk to someone,” it’s literally a button in the vehicle that you can get access.

Ed Bernardon: One of the things we started talking about at the very start here was designing and building the vehicles, and then running the services and all the infrastructure you need to deploy everything. I would imagine, and certainly, in just talking to you in the last few minutes here, I start saying, “Wow! Maybe I am feeling a little bit more comfortable now that I know that there’s a human that’s behind it all.” So, imagine, you’re starting your service, you want people to be happy, and you want people to actually use your service – I would imagine you need some sort of a campaign. I don’t know if it’s an ad campaign or somehow to inform, “Hey, it’s gonna be okay.” Is that part of it all? And how do you go about even doing that?

Mark Rosekind: So, when people ask about trust, I always say it takes three things: Data — back to our question, “How safe is safe enough?” We’re going to show you it’s safe; two, we’ve got to be transparent about that – so, to what you’re asking now, we have to have a transparency campaign that lets people see what we’ve done to make it safe and trustworthy, etc; but the third thing that’s really critical is experience. And that’s what the problem is right now. These are not on every corner. You can’t go outside your house, pull out the app, and get a ride. When that starts happening, people will get a ride in these and realize, “Oh, that was easy. That worked.” I mean, I’ve got to tell you, we do test rides in San Francisco, not in our “built from the ground up” vehicle, but in Toyota Highlanders that have our AI system on it. And when you get out and you ask the demo riders, “So, how was that?” And they say, “Well, that was boring.”

Ed Bernardon: That’s good!

Mark Rosekind: That’s what you want. It shouldn’t be too exciting. It should just be, “I can read my book or do my thing.” After a little while, that novelty wears off. That’s what you want. You’re only going to get that when you get experience. So, when all these other companies are doing demo projects and providing rides, as long as they are safe and giving experience with these things, that’s a good thing for everybody.

Ed Bernardon: Well, there’s plenty more to talk about, that’s for sure. But before we let you go, we always finish up with our section called Rapid Fire. I’m going to ask you a series of quick questions with quick answers. Are you ready to go?

Mark Rosekind: Sure.

Ed Bernardon: All right, first question: What was the first car you ever bought or owned?

Mark Rosekind: Slightly longer answer, I’ll make the others shorter. But it was before NCAP, and why that’s relevant? At 16, it was before the New Car Assessment Program with all the crash tests, and it was before that. When I was 16, a mile from my house, in my first car, somebody made a left turn and totaled my first car. So, from my first experience of driving, I’ve been in a crash that literally totaled it.

Ed Bernardon: What was the model of that car? You don’t even want to remember. Did you pass your driver’s test on the first try?

Mark Rosekind: Yes.

Ed Bernardon: What’s the fastest you’ve ever driven a car on a highway?

Mark Rosekind: Oh, well, that I can’t tell you. I tell you, I’ve gone really fast on tracks where I’m protected.

Ed Bernardon: Give us a track speed.

Mark Rosekind: Over 100. Professionals, they know what they’re doing. Learned an awful lot.

Ed Bernardon: Have you ever gotten a speeding ticket?

Mark Rosekind: No.

Ed Bernardon: No? Well, that’s impressive.

Mark Rosekind: Except, the quick one, I’ll tell you is, in San Francisco, going over those hills. Because, again, I always stop before the line and I’m sliding down. On the fifth one, I’ve got to go a little further into the intersection. And sure enough, there was a motorcycle cop who saw me do that and gave me a citation. This was literally, I think, in high school, and I’m sitting there thinking, “What would dad think?”

Ed Bernardon: Now, I want to ask you about the living room on wheels. Imagine you’re taking a five-hour road trip in an autonomous car, your living room on wheels. Like you say, you’re not driving, you can do whatever you want, you are free now to design the ultimate living room on wheels for a five-hour trip. What is in your living room on wheels?

Mark Rosekind: I want it all. I want to be able to sleep. I want to be able to watch on a big screen. I want to be able to communicate whoever I need to, and maybe get some work done too. So, I’d like it all.

Ed Bernardon: What person, living or not, would you like to spend that five-hour trip with?x

Mark Rosekind: My father. I mean, I lost him early. I would love five hours to talk with him.

Ed Bernardon: What car best describes your personality?

Mark Rosekind: Safe, electric, high-tech, and fun to drive.

Ed Bernardon: What model would that be, you think? If you had to pick a model.

Mark Rosekind: That’s what’s fun about shopping. Try to meet all those characteristics.

Ed Bernardon: Greatest talent, not related to anything you do at work.

Mark Rosekind: Well, here’s the secret. So, since fifth grade, I’m a magician. So, another one of them on here, literally, was an astronaut I taught to do a magic trick in space. So, we’ve done things literally out of this world.

Ed Bernardon: I guess without gravity, it gives you a lot of other possibilities. Can you give us a magician secret for a no-gravity environment? There’s my next question.

Mark Rosekind: It was a card trick with mission control. Mission control picked a card and the astronaut actually had predicted that card up on the space shuttle, and when he opened the deck, there it was.

Ed Bernardon: Maybe someday in the Zoox vehicle, there’ll be a button press and you can do some magic trick for us. Do you think that’s a possibility?

Ed Bernardon: That’s part one of our talk with Mark. Join us again in two weeks when we’ll continue our discussion with Mark on safety in autonomous cars. And as always, for more information about Siemens Digital Industries Software, make sure to visit us at plm.automation.siemens.com. And until next time, I’m Ed Bernardon, and this has been The Future Car podcast.

Mark Rosekind – Guest, Chief Safety Innovation Officer Zoox

Ben is the founder of Fering Technologies. He has devoted his career to whole-vehicle design, predominantly in motorsports and supercar design and is the brains behind the Fering Pioneer. He previously worked for Ferrari and McLaren, and was involved in the development of the Caparo T1 project. He has a Bachelor of Science from City, University of London.

Ed Bernardon, Vice President Strategic Automotive Intiatives – Host

Ed is currently VP Strategic Automotive Initiatives at Siemens Digital Industries Software. Responsibilities include strategic planning in areas of design of autonomous/connected vehicles, lightweight automotive structures and interiors. He is also responsible for Future Car thought leadership including hosting the Future Car Podcast and development of cross divisional projects. Previously a founding member of VISTAGY that developed light-weight structure and automotive interior design software acquired by Siemens in 2011. Ed holds an M.S.M.E. from MIT, B.S.M.E. from Purdue, and MBA from Butler.

If you like this Podcast, you might also like:

- Sustainable EV Global Circumnavigation with Ben Scott-Geddes, Fering Technologies – Part 2

- Carlo Mondavi’s Autonomous Electric Tractors for Sustainable, Affordable Farming – Part 1

- The Next Leap for Electric Vehicles with Will Graylin, Indigo Technologies – Part 1

On the Move: A Siemens Automotive Podcast

The automotive and transportation industries are in the middle of a transformation in how vehicles are designed, made, and sold. Driven by an influx of new technologies, consumer demands, environmental pressures, and a changing workforce in factories and offices, automotive companies are pushing to reinvent fundamental aspects of their businesses. This includes developing more advanced and capable vehicles, identifying new revenue sources, improving customer experiences, and changing the ways in which features and functionality are built into vehicles.

Welcome to On the Move, a podcast from Siemens Digital Industries Software that will dive into the acceleration of mobility innovation amid unprecedented change in the automotive and transportation industries. Join hosts Nand Kochhar, VP of Automotive and Transportation, and Conor Peick, Automotive and Transportation Writer, as they dive into the shifting automotive landscape with expert guests from Siemens and around the industry. Tune in to learn about modern automotive design and engineering challenges, how software and electronics have grown in use and importance, and where the industries might be heading in the future.