How to stay cool in the summer

Using readily found items around the house, you too can keep cool

It’s hot in England. 30°C / 86°F in the shade kind of hot. Since most of our buildings are built with bricks that retain heat, we don’t even get any relief at night when the temperature drops. As most of us are working from home and can’t even escape to the office during work hours, how can we stay cool in the summer? You could keep visiting your local supermarket but that can get tiresome pretty quickly and I’m not sure how your manager(s) would feel about that.

Hot, hot, hotter!

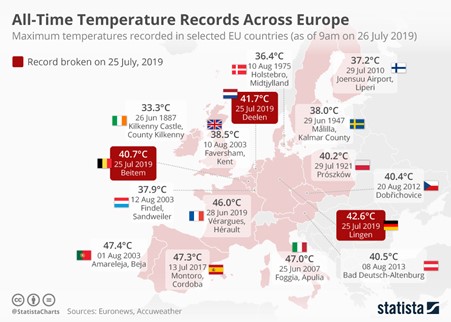

While you expect warmer days in the summer, +30°C temperature days are becoming more and more frequent in the south of England. And we’re not the only ones feeling it. For example, let’s take July 25th, 2019. The temperatures recorded at 9 AM in a handful of European countries were unbelievable:

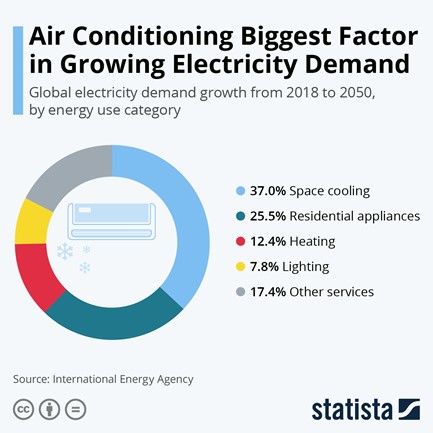

When it gets hot, most people reach for the AC (if they have it). According to Statista, there are an estimated 1.9 billion AC units in the world (2020). While most of them are in the US, China, Japan and South Korea, the landscape may change in the next 30 years. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that the number will increase to 5.5 billion units globally by 2050. This changing landscape will require a lot of energy:

Since space cooling will require a greater portion of our energy supply, naturally people are concerned about the environmental impact. According to the BVA; Société d’Édition de la Presse Régionale survey of 1200 respondents in France in 2019, nearly 74% of respondents declared that they would be willing to stop using AC during heat waves because of environmental issues.

I’m sure the other 26% have their reasons but it’s good to see that a majority are willing to make a difference.

Kinder to the environment way of cooling

Now I don’t know about you but concentrating when it gets hot (above 26°C/79°F) becomes difficult for me. I mean we’re talking brain fog territory. And when it’s more than 30°C/ 86°F then everything takes double effort. Yesterday even my laptop fans were revving so much that I thought the poor thing was going to give up the ghost.

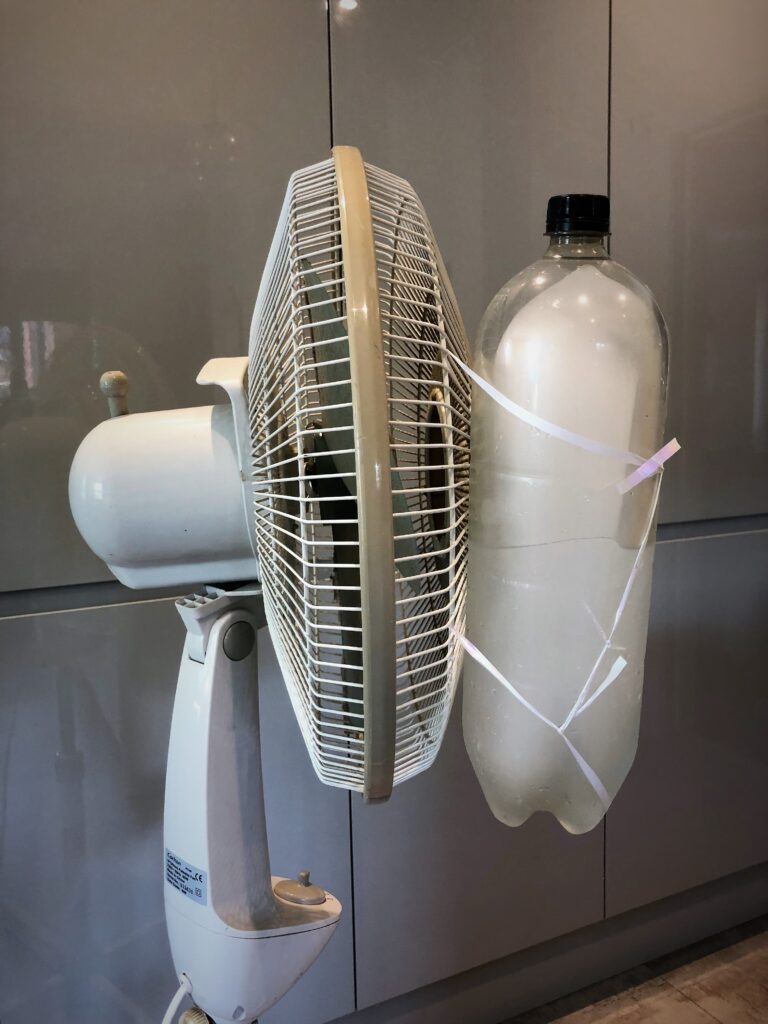

While I was complaining about the laptop noise on our group MS Teams chat yesterday, the conversation turned to how to stay cool in summer. You see they’re the team behind Simcenter Flotherm software so they’re experts in cooling. One member of the team mentioned putting a frozen bottle of water in front of a fan but there was a bit of discussion about whether it is best to put it in the front or behind the fan.

So of course, we did what any self-respecting bunch of curious cats would do. We turned to simulation!

Downstream or upstream?

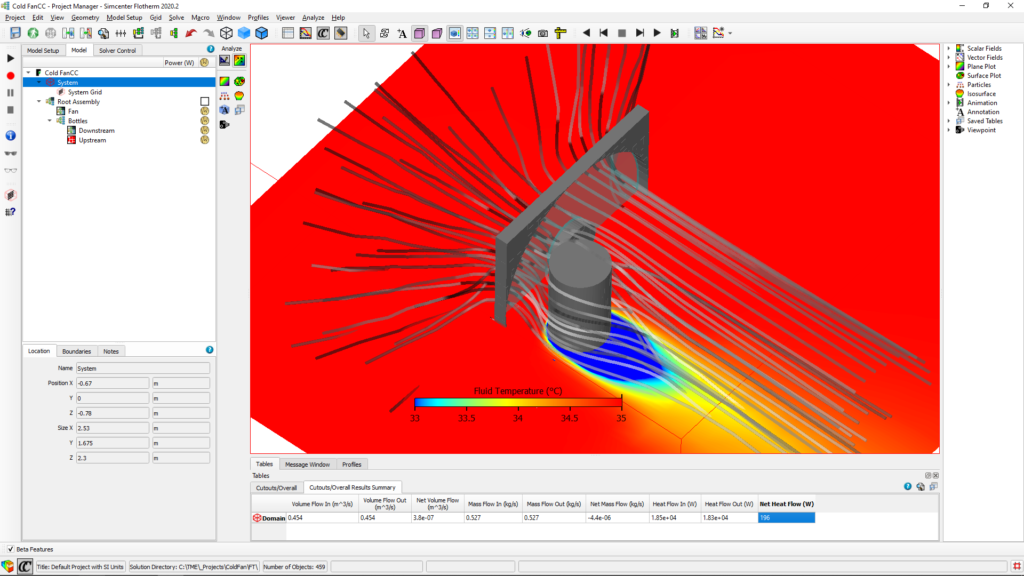

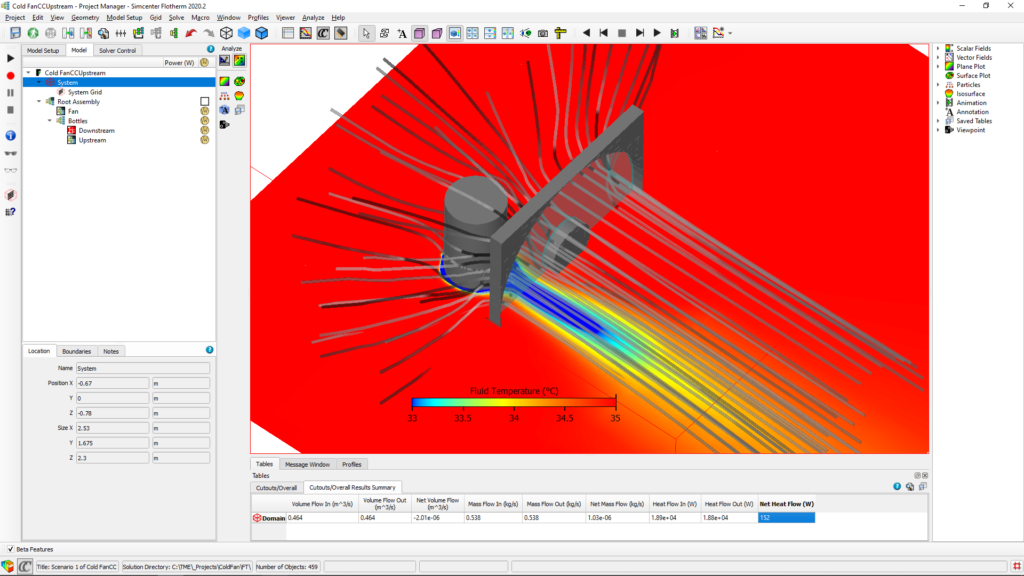

A model was quickly created with the help of Simcenter Flotherm and the two scenarios were tested – with the bottle behind the fan (upstream) and the bottle in front of the fan (downstream):

Comparing the results, we see that having the bottle in the front of the fan (downstream) is 27% better.

Of course, looking for an excuse to test it IRL, my colleague Debbie set it up and reported a huge thumbs up! And she added a footnote that the resulting condensation and drips need to be caught in some sort of vessel. And that’s why the combination of simulation and testing is better 🙂

There you have it. A nicer, kinder to the environment, way to stay cool in the summer by using what you already have at home. Thanks to CFD and Simcenter Flotherm for helping me figure it out. Now time to put my own bottle in the freezer!

PS I did mention that this was a group discussion so I’d like to take a second and thank John Wilson for his simulation magic as well as Michelle Wragg and Debbie Searle for the idea and physical testing respectively.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Hi,

Simulation images show 196W downstream and 152W upstream net heat flow. Then, how downstream is more efficient?

Hi,

Good question! I think there are two ways to answer this question. In terms of how we determined efficiency, the net heat flow, in this example, is the difference between the heat coming in and the heat leaving. Where the heat flow is determined by mass flow rate x specific heat capacity x temperature. In the downstream scenario the bulk temperature leaving was lower than the upstream scenario which results in a higher net heat flow. If you look at the two columns adjacent to the highlighted cell it lists the heat flow in and out. In terms of why it is more efficient I think the downstream scenario results in a higher heat transfer coefficient at the surface of the bottle due to the impinging flow. I would imagine that if you did a design study where the bottle was moved further and further away from the fan, the upstream and downstream scenarios would be similar.