Connecting the World with Byte-sized Satellites, Sara Spangelo CEO SWARM – Podcast Transcript

Close your eyes and imagine you’re holding a grilled cheese sandwich. Better yet, make one. Now, holding this crispy, gooey sandwich in your hands, would it surprise you to know that a device this small is capable of connecting the world? When we picture a satellite orbiting the Earth, we tend to imagine huge, complex machines. But the next generation of satellite technology has arrived, and it’s quite literally the size of that sandwich in your hands. These tiny satellites have great potential for the world at large. Their size and affordability mean they’re accessible to more people across the globe, and that they are able to reach where bigger, more robust satellites cannot. Forty-five of these satellites are already orbiting the planet, and the significance of that for farmers in remote regions, truck drivers on the road, water preservation, and the monitoring of the Earth’s magnetic field, is huge.

This is a transcript of the episode in the Women Driving the Future series, where we interview interview Sara Spangelo, the Co-Founder and CEO of SWARM, a satellite company working to link the world through reliable, low-cost internet connectivity. Her expertise in small satellites and autonomous aircraft, paired with her background as a lead systems engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and Google X, has uniquely positioned her to become an industry leader in the pursuit of global connectivity. We talk about how the concept of such tiny satellites came to be, the numerous benefits of their use from individuals to companies alike, and the impact they’ll have on the future of transportation and space travel.

Ed Bernardon:

When you imagine what it will be like to commute to work in 20 years in our living room on wheels, we assume we’re in a fully connected world where we instantly talk to anyone anywhere on the globe at any time. These two components of our driverless future go hand and hand but they also present very different obstacles to overcome. Designing an autonomous vehicle that operates in New York or LA or any other urban center with high connectivity has vastly different requirements than one operating in somewhere like an African deserts or a winding mountain road in the Himalayas, or even Antarctica. But luckily there are those working to bring our connected world to every corner of the globe.

Welcome to the Future Car Podcast, I’m your host Ed Bernardon VP Strategic Automotive Initiatives at Siemens Digital Industry Software. Usually we keep our feet on the ground, well, our wheels on the ground, But today, we’re going to venture out into space. Next in our series “Women Driving the Future” we talk to CEO and founder of SWARM, Sara Spangelo. SWARM has developed an innovative grilled cheese sized affordable satellite that is bringing connectivity to some of the most remote corners of the planet. While the race for more and more data to 5, 6, or 7G someday continues between cell phone providers, But Sara and SWARM have a different approach, to bring a small but highly valuable and useful amount of data to those that would otherwise have none at all using a swarm of satellites orbiting our planet that you could literally hold in your hand. I talked to Sara not only about how SWARM is helping bring us into a fully connected world but we also explored how she got to where she is today, what it takes to become an astronaut and even what life is like in Antarctica for all of you looking to book a vacation in 2021 to the frozen south.

Welcome to the future care podcast, Sara!

Sara Spangelo: Well, thank you for having me. I’m glad to be here.

Ed Bernardon: 2020 has been an exciting year for SWARM. You came in number two, right behind SpaceX in Fast Company’s Most Innovative Space Companies for creating a, what’s called a grilled cheese size, affordable satellite. Tell us what is SWARM? What do you do? What’s your mission?

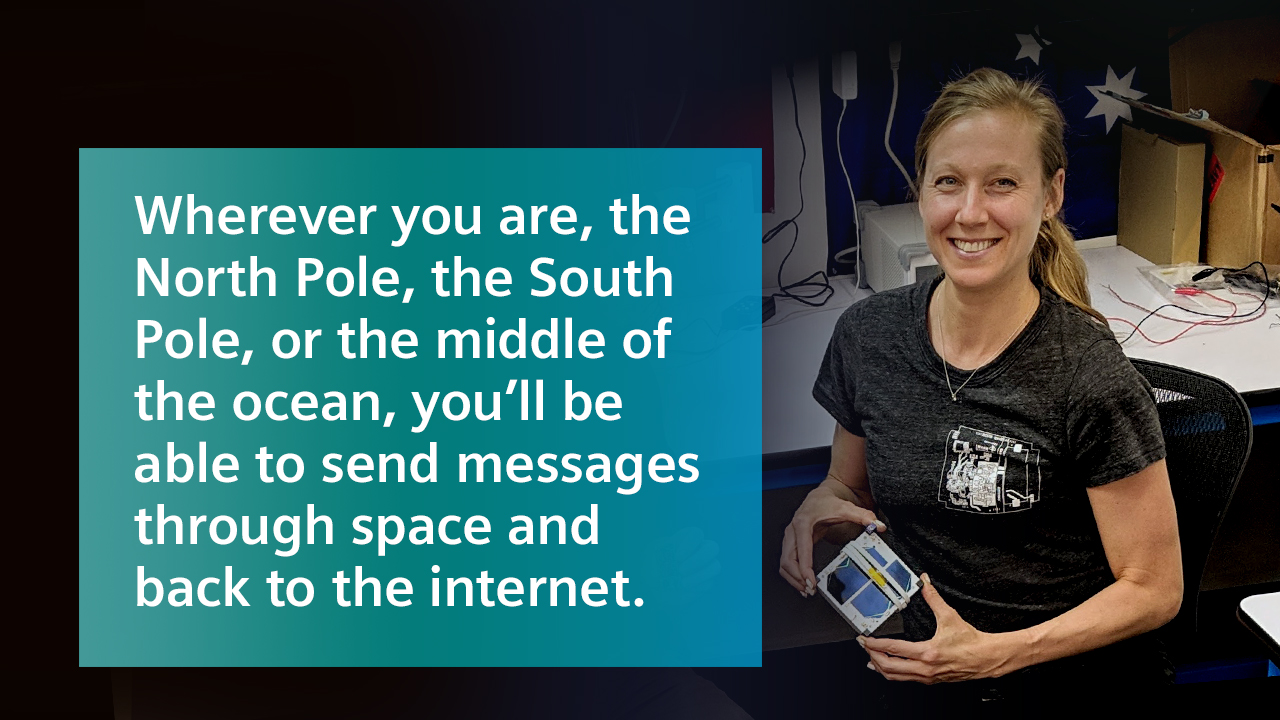

Sara Spangelo: Absolutely. That was a very exciting milestone for us as well. We’ve accomplished a lot in 2020. SWARM started actually about four years ago. Our goal when we started was to make a low-cost satellite connectivity solution. Today, if you want to buy a satellite, it’s typically really expensive, really difficult to buy really large equipment, difficult to integrate, and really reserved for private jets, big ships, aircraft carriers, and things like that. We recognized a gap in this space about four years ago. We figured we could help solve this with a really tiny satellite. We actually were motivated to develop the smallest satellite possible, that’s because the smaller the satellite, the lower cost it is to launch it. Many people have probably heard of small satellites or even cubeSATs, these have become really popular over the last 20ish years, we were able to develop the world’s smallest satellite. So, about 12 times smaller than the conventional small set of the 2010s era. Our satellite is, like you said, about the size of a grilled cheese sandwich. Specifically, it’s 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters by 2.5 centimeters, you can literally hold it in your hand, which is pretty incredible. We’ve so far put up 45 of these satellites, 36 of those are for our commercial network. We’re planning to deploy a total of 150 commercial satellites. Once all 150 are up, they will actually cover the whole globe. So, wherever you are, even if you’re at the North Pole, the South Pole, the middle of the ocean, you’ll be able to send messages through space and back to the internet. Actually two ways you could also send commands up to devices that might be floating on a tuna fishing buoy out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. We’re able to do that at a really unique price point because our satellites are so small, and just to give a reference, it’s about four to 20x lower cost relative to the next lowest cost satellite today. We actually announced our products and pricing a few months ago, the prices are super affordable – it’s $5 per device per month, which starts to feel a little bit like a cellular plan. That’s the first time that the prices have been so low in such an innovative way of solving for connectivity. We’re really focused on bringing back data from sensors and assets that might be anywhere on earth, and a lot of our verticals are things like agriculture where we’re bringing back a sensor reading from like a moisture sensor, logistics, tracking trucks and ships and container ships, things like energy. So, bringing back values from oil and gas, solar and wind monitors out in the wild, and then maritime is another big vertical, bringing back small amounts of data from buoys that are doing environmental monitoring or fishing boats, so things like that. In the future, we’ll also start to connect people more, which will also become a really exciting part of our business.

Ed Bernardon: How does one become the CEO of a satellite company? When you were little, I bet you loved to play with model rockets.

Sara Spangelo: Not really, I definitely played a lot of Lego when I was little – the basic ones, not the fancy ones; we had to build our own windows and everything. I also grew up doing ballet and swimming. So, pretty girly stuff. I did, however, get introduced to space stuff in middle school. I had the opportunity to go to space camp when I was in grade eight and bounce on the moon wall and do representative missions, mission control, things like that. That definitely got me very excited about space and exploration and potentially being an astronaut. I think that’s really what led my route to some of the educational and professional choices that I made later in life.

Ed Bernardon: Is that when you trade it in the ballet slippers?

Sara Spangelo: I had to trade in the ballet slippers. I remember, I did my undergrad in Mechanical Engineering and did space courses and had a super heavy workload. There got to a point where I had to stop. I was actually teaching dance. I had to stop teaching dance because school was taking over. So, it was like ballet or mechanical engineering courses and projects and things like that. I think I was maybe 20, so I managed to do it for pretty long into my university life but then had to eventually pivot to other things.

Ed Bernardon: You might be probably the first ballerina to ever convert to being a rocket scientist.

Sara Spangelo: You know what? I actually know one more. I worked with here at JPL. There’s actually a handful of women CEOs that I know doing space or tech companies that may have done ballet when they’re younger – I should do a survey. I don’t think it’s that uncommon.

Ed Bernardon: You’re working your way into middle school and now your interests are starting to shift. Tell us more. Now, you’re into space, rockets, and telescopes. What happened next?

Sara Spangelo: I think at that point, I’d always been a very strong student. I think I probably could have gone into medicine, if I wasn’t scared of blood and needles, or become a professor, anything, really. I think at that point, I probably narrowed my focus more to the physics and math courses in terms of the AP classes I took in high school and things like that, from maybe some of the arts. I was never particularly good at music or art or anything like that. Just more of an emphasis on the physics, chemistry, and even biology I did take in high school and university, and then it led me into, when I entered university, I actually started in just doing sciences. I was studying all of the sciences. I was a little bit of a rebellion, I have to admit, my parents are both civil engineers and my grandfather was a mechanical engineer, and I thought, “Ugh! Engineering.”

Ed Bernardon: Did you make your grandfather happy or your parents happy, then, at first?

Sara Spangelo: I think it was just neutral because I didn’t pick engineering. Then after about a year, I realized if I’m going to be able to study the really cool stuff and work on projects with the impact, I should probably go into the engineering department. The opportunities there were a lot more significant in terms of internships and paths to careers. Then I shifted to mechanical engineering and that’s actually the degree that my grandfather has from the same school. So, I got the same degree, the same school, about 50 years later. But I got the gold medal and everything, which is like the top grades in that program, which wasn’t very competitive, by the way. I think he was very proud when that happened. And yeah, my parents were chuckling when I eventually threw up my hands and said, “God, I better go into engineering.”

Ed Bernardon: You had a general direction, that’s more than most people have. At least you knew it wasn’t ballerina, it was definitely going to be engineering, and then you narrowed down a little bit more. Now, you’re a pilot, did you learned when you were in grad school or undergrad to fly a plane?

Sara Spangelo: I’ve done a few test lessons when I was in grad school, but I really started once I graduated, then it was kind of a reward to myself for four and a half years of grueling work in Michigan, underground, winter, just like working constantly. It takes a lot of time and money, so it’s pretty difficult to do when you’re in grad school. Some people managed to do it, I didn’t have that ability to multitask; I was very focused on school at that time. I started once I graduated and started that in Michigan and then continued when I moved to Pasadena when I took my first job at JPL and completed it in Southern California, which is a great place to fly, generally, weather-wise. That was a fun thing to do after grad school, for sure.

Ed Bernardon: But it was in grad school, then, that you made your hard turn into space, shall we say?

Sara Spangelo: When I started at the University of Michigan, in aerospace engineering, that was when I made that pivot to aero versus mechanical engineering.

Ed Bernardon: Was there a moment or someone that really inspired you?

Sara Spangelo: At a really high level, astronauts like Chris Hadfield, who’s a famous Canadian astronaut, I’ve seen growing up and I always thought that was very inspiring. I actually got to meet him last summer, which was mind-boggling. I sometimes email him and he actually answers, that’s pretty cool. And then I’d say, growing up, I also had more entrepreneurial examples. The woman that actually ran my dance school was an entrepreneur and a dancer, Shelly Sheer. I found her very inspiring in terms of her career path. She kind of decided, “I’m going to do this.” It was kind of crazy but she did it and she was very successful.

Ed Bernardon: At this point, you mentioned you were speaking with an astronaut that inspired you, did you think at that point, you might become an astronaut?

Sara Spangelo: No. I think you always know that that’s a really far off dream. I mean, everyone in the aero department in Michigan, everyone at JPL, and everyone at Google would say they’d love to do that. But I think everyone’s like, “Well, the chances are extremely slim that it would be me.” It sometimes drives us, educationally or professionally, to do certain things just because, “Oh, I could open up that door to potentially do that thing.” But I think, at least for me, I was thinking, my chances of this are basically zero. So, being more realistic and then you get more realistic or maybe jaded as you get a bit older.

Ed Bernardon: You were named, though, one of the top 32 Canadian astronaut candidates.

Sara Spangelo: Surprisingly, I made it that far. But they only picked two, so I wasn’t that close. But it was a really cool experience to go through. We got to do lots of mock simulations and physical and psychological tests. I got to meet the people that became the astronauts and all the other wonderful Canadians. So, that was a very cool experience. I’m glad I got to go through it.

Ed Bernardon: Well, you said there’s psychological and physical testing, what was the hardest test you had to take to see if you were suited to be an astronaut?

Sara Spangelo: I think the hardest thing about it was actually just the intensity of being in an environment for three or four days, where it was just like test after test after test, you have no idea what’s coming. You feel like this wild race. I think if I had to pick one specific test, there was a test where we did this water-based testing in a facility in Halifax in the middle of the winter. It was kind of crazy.

Ed Bernardon: Freezing cold water.

Sara Spangelo: It was inside but when you go outside it was freezing. We’re in this simulated helicopter that got plunged underwater and then it flipped upside down, which actually happens in helicopters.

Ed Bernardon: So, that was on purpose, then?

Sara Spangelo: Yes, on purpose. And you had to unbuckle yourself, find the door, escape, and obviously, hold your breath for that period of time. That was probably like going into that, the scariest thing because it’s like I could actually drown, or if I mess up, like, I’m going to come out the wrong side, or I’m going to bump into something or I can’t find the door and it’s going to be such a tight window of time and I could only hold my breath for, whatever it is, 40 seconds, maybe a minute if you’re lucky. I really have to figure it out quickly.

Ed Bernardon: You obviously did it though. Obviously.

Sara Spangelo: I did it. Honestly, it wasn’t that hard because there were tricks that you could use like holding on to the side and knowing that I have to hold my breath for five seconds, open my eyes, unbuckle, look left, do a 180 and go out that window. If you have the procedure in your mind, it’s actually pretty straightforward. I remember coming up and being like, “I’ve tons of air left, I could have stayed longer.”

Ed Bernardon: I’m going back.

Sara Spangelo: No, I’m not going. But that was pretty cool to get through that. There were some really highly-trained Navy SEAL type people there, that was part of their normal training. So, for me, a total civilian, untrained person to be able to do, it was cool. But that was probably the most nerve-wracking going into that.

Ed Bernardon: You get out of grad school, you have your first few jobs there JPL. When did you know you had to start SWARM? How did it all come together?

Sara Spangelo: It was honestly very organic. After JPL, I actually went to Google X, where I worked on the Project Wing, which is a drone delivery company. I also worked on some secretive projects there, which allowed me to experience a little bit of entrepreneurship. So, proposing things internally, being able to justify them to investors for a team, pitch an idea – that was a great experience for me. And then around, late 2016, my co-founder and I, then, were tossing around the idea of, “Wow, no one’s really solving for the lower end of connectivity.” There’s Project Loon, which is held through balloons. Facebook had a solar-powered UAV project. There’s SpaceX, there’s one web, all of these really highly capitalized, constellations were being proposed and we were like, “Wow, these are going to cost billions of dollars and take five or 10 years and may fail.” Actually, two of those four projects have now failed or gone bankrupt. So, our feelings around that were totally correct, and we thought we could do something really interesting with really tiny satellites. So, that’s really where it started. And then it was like, “What’s the smallest satellite we can develop? What’s the data rates we can get with that? Is that useful for some of these IoT applications?” It’s very, very iterative, very organic. We spoke to our flight instructor, we were practicing flying here in the Bay Area, and she was kind of like, “That sounds like a pretty interesting business opportunity. Do you want to speak to investors?” And we were like, “Maybe. Yeah. Okay, sure. Yeah.” And then introduced to some investors and then resulted in one industry being really excited on SWARM and they gave us a term sheet. It’s not a typical story. We’re very grateful that we had a relatively smooth transition. It was very organic.

Ed Bernardon: I was a founder of a startup as well, and there’s the technical side, but then there’s also just a passion or drive. It seems that for you, you had your inspiration in grad school with the astronaut. But also, I bet that entrepreneurial spirit that you learn from your ballet instructor, those two must have come together at that point.

Sara Spangelo: I think so. It’s all in the background but I think that I, probably deep down, was always thinking, “Oh, I’d love to start something.” And I actually did start a party planning business when I was little, and I did like an arts and crafts program, and I babysit a lot. So, I was actually entrepreneurial when I was like, 11. I think it was probably in there but I think I didn’t think that I would have the opportunity or the skills to actually do it ever, so I never really voiced it. But I don’t know, one foot in front of the other, and over time you figure stuff out, we’re still figuring out a lot of stuff on SWARM.

Ed Bernardon: The CEO of rideOS, he was in the booth next to you at CES when we met. He had the same entrepreneurial spirit when he was small. His business, when he was little, was selling turtles. So, there you go, you never know. Let’s talk about SWARM – affordable connectivity is very, very important – what made you decide to shape your company around this goal of affordable connectivity?

Sara Spangelo: Again, it was pretty organic. It was, in 2016, looking at what a lot of new companies were focusing on, which was connectivity and recognizing that’s a big problem in our world, 90% of the surface area is not connected of the earth, which is crazy. And even, I live in Portola Valley, there are pockets where there’s zero cell connectivity, which is just crazy in our day and time.

Ed Bernardon: What’s that percentage in the United States, you think?

Sara Spangelo: It’s actually really tricky because there’s a lot of claims that highways and farm fields are connected but if you actually talk to the farmers or the logistics people, they’ll tell you that cells are actually very weak and often zero in those regions. We think that it’s probably something like 30% or 40% cause connectivity.

Ed Bernardon: When you see that T-Mobile map, it looks like it’s all pink except for a couple of spots here and there. So, that’s not 100% correct, then.

Sara Spangelo: It’s not. Maybe that’s what they think they have or they’re striving to achieve but cell phone towers are challenging, and if there are obstructions, interference, just doesn’t achieve the range, that all impacts performance.

Ed Bernardon: How do you go about creating affordable connectivity then? You want to get that 10% up to a bigger number, how do you do it?

Sara Spangelo: Right now, the 10% that has coverage today is largely cell phone tower based. There’s cell phone infrastructure that most of us connect to on a daily basis in and around cities. The challenge with that, of course, is that it doesn’t extend beyond cities, we’ve all experienced, driving on a highway away from the main city and losing cell connection. And that’s particularly challenging if you have a lot of assets that are out of cellular range, in a lot of the verticals that we’re focusing on in agriculture, logistics, maritime, energy. The way we’re approaching it is we are putting up these tiny satellites, which is relatively low-cost to do as far as satellites go, and then providing a way to connect to devices on the ground. You can almost think of it as a walkie-talkie in space. We manufacture these small modems, kind of like a cellular modem that we call a tile, that gets embedded within an asset tracker or an agricultural sensor. And then an antenna is attached and the antenna is relatively small, it’s just eight inches high, and that sends little messages, you could think of them as little tweets, to our little walkie talkie device, which is our satellite in space. And then messages get down-linked to ground stations on the ground and then connected to the internet. It’s really that simple.

Ed Bernardon: When you say small, what’s the size of a typical satellite and cost? What’s the cost and weight of a typical satellite versus a SWARM satellite?

Sara Spangelo: Typical is funny, but I think the typical satellites that are providing a similar service to SWARM are usually several 100 kilograms, or even of 1000 kilograms and are usually several million to put up to build and launch. And then a SWARM satellite is about 400 grams, about a thousand times smaller. I can’t tell you the price but it’s a lot lower than several million. I will tell you that we can put up our whole network for far less than what we raised in our series A, which was 25 million.

Ed Bernardon: I suppose I can’t buy one on Amazon, though. It’s not that cheap.

Sara Spangelo: No, not yet.

Ed Bernardon: What’s your business model like? How do you make money with this?

Sara Spangelo: The way that we make money is it’s pretty simple. It’s kind of like a cell phone model. We first sell these modems, that we call our tiles, and we’ve just released our pricing, they’re 119 US each, retail. You would embed that within your product, whether that’s an asset tracker, or a moisture sensor, and an agriculture device. And then we charge customers $5 per device per month, which is kind of like what you would pay for your cell phone plan. And that allows you to move a certain amount of data, a certain number of messages. It’s really that simple. There’s no additional setup fees, or annual fees, or monthly fees, or anything else crazy. It’s just that simple. And the antenna actually comes with a tile, so you don’t need to buy anything extra, it’s all included in that pricing.

Ed Bernardon: On your website, it said, “For $5 a month, you get 750 data packets per device.” There are 200 bytes in a data packet, and so I did some calculations, I don’t know if I got it right or not, but that’s like 15 kilobytes per month or 500 bytes in a day. That’s not very much data but it must be valuable though.

Sara Spangelo: It’s about 150 kilobytes per device per month, divide by 30, that’s about five. You’re right, it’s not much data. But it’s enough data to be very valuable for many of our customers. And the reason being, right now they have these devices floating out, in the ocean or in an agriculture field, or on highways, and they have no idea where it is, its health and status, its temperature. It’s really valuable to know where the device is. We find a lot of different value propositions that SWARM provides but I think the biggest one is often replacing humans having to do something really annoying and time-consuming and potentially dirty and dangerous, like driving out, take and writing down the meter reading on every single electrical meter across the highway, or calling up every single trucker to ask, “Where are you?” And that can be someone’s full-time job can now be completely eliminated and they can have a much safer job and more pleasant job by being able to bring back these sensor readings basically automatically and having them load into a platform or a dashboard on the computer and eliminating a lot of the confusion, mistakes, and time and energy that’s required for humans to do those jobs today.

Ed Bernardon: We’re always hearing 3G to 4G to 5G, gigabytes of data, hundreds of megabytes of data and videos and all that, and always striving to send more data. But on the other hand, an example you’ve mentioned before and is on your website, that 50 bytes of data could probably save your life; say, you’re lost in the woods, a plane crash, on a remote mountain, or who knows what it might be. It doesn’t take a lot of data to be very, very valuable, it seems like.

Sara Spangelo: Exactly. That’s really where our sweet spot is, it’s connecting places on earth that typically have had no other solutions, where the other solutions have been prohibitively expensive. I envision that someday SWARM will save lives. But it will also have a huge impact in things like monitoring where trucks are and how fuel-efficient they’re being, where food supplies are and how efficient their transfer is, or if the temperatures are appropriate, so preventing things like food spoilage and waste, preventing extra CO2 emissions, having better monitoring for fires, obviously, that’s a big thing here in California, if we could monitor where the fires occur, or in Australia, then we could have a better opportunity to fight them, and doing things like ocean and air monitoring to have a better idea of what’s going on with climate change in the environment – there’s a lot of other impacts we can have. One of my other favorites is tracking animals, being able to track endangered animals, whether that’s whales or other land-based creatures, there’s been several people approached us, wanting to stick devices onto these animals, just to track where they are and making sure that they’re healthy and they’re where they’re supposed to be to prevent any poaching or negative things that could happen to them. There’s a wide range of crazy applications for SWARM. You learn more about this every day,

Ed Bernardon: When you think of a lack of connectivity, you generally think of rural populations. And in fact, you mentioned, again, on your website that farming is one of the least digitized supply chains. How is this going to help that?

Sara Spangelo: Several aspects of industrial agriculture are actually pretty advanced, they do a lot of sensing and a lot of automation, but there’s always connectivity challenges in these remote regions. Where I grew up, in Manitoba, in Canada, as soon as you go outside of Winnipeg, there’s basically no cell connectivity and there are farmlands for days and days and days across the prairies. Farmers were able to have sensors on their fields that could send back data autonomously to the internet into their dashboards. It could help them make informed decisions. Do I need to water? Is it time to bring in my crops, and other key insights about temperature, humidity, that helps them make smarter decisions about how to use limited resources? Here in California, there are some new regulations coming out about groundwater management, and having SWARM enabled devices that can let farmers know where water levels are, can be very informative to make them be able to make smart decisions about how to use water more effectively.

Ed Bernardon: I was surprised to hear that in California, they spent $4 billion a year watering crops.

Sara Spangelo: Yes, it’s crazy.

Ed Bernardon: Specifically, can you give us an idea? How does that actually work? How can I reduce that 4 billion with SWARM?

Sara Spangelo: It’s not a super simple equation but if you’re able to know where the water levels are – if it’s rain, for instance, you may decide, “Oh, the water levels are sufficient, I don’t need to water my crops.” And in fact, “I shouldn’t water my crops because maybe I’ll damage them.” Alternatively, if it’s really dry and you recognize, “Oh, I need to spend time, right now, watering.” You have that information. But you can also make smarter decisions about how often water usage is metered and the time of day that you use it can result in different charges. You may choose to water at night because you have the information that you’re approaching your drought or watering is critical. But you also have the information of the various fees that you’ll be charged, you can make smarter, more informed decisions. That’s how it can help cut down on costs and reduce waste.

Ed Bernardon: All it takes is those couple of bytes that say, “This is how dry the soil is.” And being able to collect that over a wide area very, very easily, and knowing that it’s always going to work.

Ed Bernardon: economically disadvantaged communities may not have access to technology but this can provide that as well.

Sara Spangelo: Absolutely. Yes, we’re very excited to support a lot of the global development efforts in developing nations. It could be things as simple as monitoring if a pump is working, the air quality, the water quality, and Sweet Scents is one of our first partners and exploring what SWARM can do in those areas.

Ed Bernardon: When you launched your first satellites, how did you make a decision on what part of the globe you’re going to light up first with connectivity?

Sara Spangelo: Actually, the orbits that we select are really interesting, they’re called polar Sun-sync orbits. You can think of this as an orbital plane, or I think of it as a hula hoop, that’s around the outside of the earth. It actually stays fixed relative to the sun and it rotates around the sun as the Earth rotates around the sun, and the earth spins underneath of it. We actually didn’t need to pick a region because our orbits see every point on Earth, usually about four times a day, in a single orbital plane. We launch many satellites into that orbital plane and we have a trick that spreads them out relative to one another, kind of like a string of pearls – by doing that, we get this great coverage. And then we launch our satellites into different orbital planes, you think of it as two hula hoops that are locked 90 degrees from one another. That’s actually what we have right now, we have two different orbital planes from our two most recent launches. And then we’re going to fill in different orbital planes, until it looks like an orange with all the wedges cut out. That’s the visual that I typically share. You can actually see this on our website swarm.space. And then we have total global coverage, every point on earth is covered at all times, which is a nice value for our customers.

Ed Bernardon: I think the total is 150 satellites to cover the entire globe. Is that what it’s gonna take?

Sara Spangelo: That’s right, you did your research.

Ed Bernardon: Well, I also went and played around with your satellite tracker. It is very cool, because you have this globe and you can turn the globe around, and it had a single polar orbit on there. It looked like satellites, like, one through nine or something were on there, and then there’s closely bunched another group of them, they’re all together there. But pretty much they’re all on that line of the polar orbit, except number eight. You call these space bees in the spirit of SWARM. All of them are on the line, but poor little space bee number eight or nine, I think it was, was off to the side there. Is space bee number eight okay? Is everything going all right over there with that one?

Sara Spangelo: Space beeseight and nine are just in a differenttype of orbit, and unlike the polar orbit that I was describing that goes pulled a pole that stays like these lock tool hoops, it’s actually inclined at 45 degrees. So, think of if it was a dinner plate around the equator, and then it’s tilted up halfway, 45 degrees. Those are just in different orbits because those were experimental satellites. So, it didn’t matter so much what orbits we put them in.

Ed Bernardon: So, they’re okay. We don’t have to worry?

Sara Spangelo: They are okay, but thank you for checking on that.

Ed Bernardon: I want to make sure your space bees are fine. Now, do you ever feel like these are your little children and they are out there and you want to make sure that you check in on them a couple times a day?

Sara Spangelo: No, I think I have that may be association with some of my employees. The satellites, there certainly is a team that has that type of love, the people that built them and hand built every single one and hand tested them, they certainly check it on them. Now we have 45, so it’s a lot to keep track of.

Ed Bernardon: Satellites have to operate in very extreme conditions. One of the things that you do guarantee, I saw on your website, is peak performance, including in the South Atlantic Anomaly, and I’m listening and I go, “Oh my God, that sounds like a dangerous place, maybe it’s related to the Bermuda Triangle or something.” What is the South Atlantic Anomaly and why when you tell someone that you have high performance there, it’s very impressive for a satellite?

Sara Spangelo: The South Atlantic Anomaly anomaly is where the earth’s inner Van Allen radiation belts come closest to the Earth’s surface. It’s a really crazy radiation environment that can be challenging for satellites because it can cause failures with the electronics. Imagine flying through a bunch of radiations is kind of scary. We do a bunch of things on our satellites, both in the hardware design as well as in the firmware design, to protect against these anomalies. Many satellites, I remember some of the satellites I worked on in grad school, which is kind of like turn off and then turn back on later when they went through the belts. It’s important for us that the satellites work all the time because we have customers all over the world. We are really proud that the satellites are performing well, even when they go through the SAA as we call it.

Ed Bernardon: Now, if you were standing right in the center of the SAA, would it hurt a person in any way or is this something just for electronic equipment?

Sara Spangelo: Oh, yeah. That would be very dangerous for a person. You’ve probably seen in space movies – most recently, the show “Away” – when the astronauts were traveling to Mars, they were inside this water module to protect them against radiation and they actually ran out of water.

Ed Bernardon: It was in the wall of the spacecraft, right?

Sara Spangelo: Exactly, that was protecting them against the radiation environment, and the ISS has something similar, although it’s not as bad as you would be once you’re outside of the Earth’s protective layers. So, yes, it’s a concern for all people and all satellites. Engineers spend a lot of time thinking about how to protect components and people from these types of radiation events.

Ed Bernardon: But the anomaly itself is actually in space. It’s not like on the surface of the ocean?

Sara Spangelo: Correct.

Ed Bernardon: Okay. So, you’re still safe; you can sail anywhere you want in the South Atlantic and nothing’s going to happen.

Sara Spangelo: We’re lucky. We’re protected inside these radiation belts on the earth. So, we have very few of these effects. It’s definitely a point up in space. I think it dips down to an altitude of about 200 kilometers, so we’re much below that, of course, on Earth.

Ed Bernardon: I want to ask you a little bit about what you do and its impact on transportation because we actually did meet the first time when you were in the Ford booth at CES, what role is SWARM going to play in the future of transportation?

Sara Spangelo: We have a really exciting partnership with Ford. They featured us in that booth, we’ve done some cool demos connecting Ford vehicles outside of cellular range with our satellites, just previous to that event, actually. There’s a few different ways that SWARM can help with transportation and logistics. For the Ford use case, they’re very interested in connecting vehicles that go outside of cellular range and have emergency situations where they would need to call home. I always think of when I was driving through snowstorms in Manitoba, from my grandparents place, which was an hour and a half outside of Winnipeg back home; if we’d gone off the road or something like that, there would have been no way to call home, there’s no cellular connectivity. So, imagine every vehicle or every Ford vehicle, having a SWARM button that you could hit, and it says, “SOS, send emergency vehicles to this location.” And of course, you have your GPS position that you can send. They’re very interested in that – connecting vehicles outside of cell range. And then they’re also interested in tracking vehicles throughout the logistics supply chain. When a vehicle comes off, when it’s first constructed, say in California, it may only have a sell chip for maybe Canada or China or India or whatever. Ford is interested in being able to track that vehicle throughout its journey until it arrives at its final destination. That’s another area where we could send, even just a small ping once a day of the position that could be very useful for Ford to keep track of all these vehicles, and help eliminate confusion and theft and things like that along the way. In the logistics space, with respect to tracking, we see a lot of need for tracking trucks and being able to send back health and status updates every hour or every day, having a backup mode of communication for the drivers to make sure that they’re healthy and safe and all of those things. And then we’re extending it a little bit more to including other types of logistics like ships and containers and shipping containers and those types of things. We’ve had early conversations with companies like Maersk and several other logistics companies that want to be able to track every container and certainly every ship with SWARMs unique price point, that becomes feasible because it’s just so much lower cost and you could almost slap one of these tiles or a tracking device on every single asset and be able to keep track of it throughout your supply chain

Ed Bernardon: In a way it brings the advantage that connectivity brings you if you’re driving a car in an urban center, it brings that connectivity and all those advantages of that anywhere that vehicle is going to be.

Sara Spangelo: Exactly. That’s a perfect way to summarize it. The one thing we don’t do is cell phone calls. So, you can’t call someone or do a zoom call when you’re driving, but you could text them, which still may be very useful.

Ed Bernardon: Now, a key part of your system is the ground stations. And one thing I found fascinating was your co-founder, and he had your ground station, which you can put in a carry on luggage, and behind him was a standard ground station, which is what we all imagine a ground station looks like this big, gigantic satellite dish pointing towards space. How can you make your ground station so small when everyone else is using these gigantic dishes?

Sara Spangelo: Our ground stations are differentiated relative to all existing satellite solutions today. You’re right, they’re a lot smaller, and therefore, they’re a lot lower cost. They require a lot less real estate and power and all of those resources. The way we achieve that, it’s partially because of the frequencies that we’re using. So, we use VHF frequencies, a little bit lower than what many of the satellite providers use. And then we’re also relatively low data rate. So, that helps us get them smaller. But I think the key thing here is that we decided to build and deploy our own networks. So, instead of relying on anybody else that already has a big dish, or a big Yagi antenna, that we would have to rent, and it would be very expensive; we decided, “You know what? We’re just going to take this on, internally.” So, by developing our own equipment, we’re able to miniaturize it and really specialize it for what our use cases. I think that is what ultimately led to them being so tiny and easy to install.

Ed Bernardon: These ground stations are located in some very remote areas, it looks like.

Sara Spangelo: That’s done intentionally so that we have nice coverage. Regardless of where someone is uploading data, they can almost immediately downlink it to one of the ground stations. Ben and I had the opportunity to go to Antarctica, which is very close to the south pole, to install a ground station. And we did carry it in our carry on luggage, which was kind of terrible. But we managed to do it all the way there.

Ed Bernardon: How do you get to Antarctica? I mean, it’s not a direct flight from New York City.

Sara Spangelo: It’s definitely not a direct flight. We did fly direct to New Zealand and then we took a military plane from Christchurch in New Zealand, straight to the base. That was sponsored through the NSF, the National Science Foundation. It’s a very fascinating operation that keep McMurdo Station, which is funded by the NSF going year-round. There are flights in and out, I think there were 1,000 people there when we went. So, it’s quite a community and they do a great job of bringing food fresh food there and maintaining all the aircraft so that scientists can do some pretty amazing research out there on the ice shelfs with all of the penguins and crazy environments that you experience there.

Ed Bernardon: What do you do in your spare time there? So, you’re done setting up your station, what do you do for fun in Antarctica? Do you play with the penguins?

Sara Spangelo: We didn’t get too close to penguins, but they have a lot of activities you can do there. It’s a really interesting community, people definitely band together and there’s all sorts of things that you can participate in. So, I’m really into working out and they had three gyms, and there was even a group that did these insanity videos, which is this type of kind of crazy workout. So, I found my people and I worked out with these six people that did insanity on the ice shelf.

Ed Bernardon: On the ice shelf?

Sara Spangelo: It was in a gym inside, but it was in a pretty remote location. And then another day, we actually took these ice bikes, which are basically kind of like beach bikes, you know, the tires are really big and rugged.

Ed Bernardon: Do they have big needles on the tires to dig in or anything like that?

Sara Spangelo: No needles. I think that the environment was sufficient that you could just have these big thick beach tires. We biked on the ice to a neighboring station. So, the New Zealand station that was set up, maybe, I don’t know, it felt like it was 10 miles away, but honestly was probably two miles away. The biking was was was pretty hard, and I was thinking this is why I do all my spin classes. I’ve been training for this. And then we biked up this crazy hill and we’re wearing our Canada Goose, the big red jackets, and I remember looking over a bed and thinking we’re on Mars.

Ed Bernardon: What am I doing here?

Sara Spangelo: Yeah, it was so cool. So, we did that. There are also lots of bars and parties, and people are very social, so we got to participate in that a little bit.

Ed Bernardon: There are a lot of bars in Antartica? What’s the top bar in Antarctica? I guess it would be the best bar in the continent.

Sara Spangelo: I don’t even know what it was called but it was pretty hopping on a Saturday night.

Ed Bernardon: Well, if you can’t remember what it was called, you must have had a really good time.

Sara Spangelo: I think we said, “It’s like 9 pm.” And then passed up. And then we also have installed stations of the Azores, which is the middle of the ocean, it’s part of Portugal, and then Hawaii, Alaska, and then all through the US; recently, Cyprus, a few other places you can probably see on our website. We continue to expand, so if you know anyone with connections with a location in a really remote island or something like that, we’d love to chat with them about putting a ground station.

Ed Bernardon: As soon as I meet a remote island owner, you are the first person I’m going to call, I promise. Let’s talk about the future here. Once you’ve achieved your goal of lighting up the world, what comes next?

Sara Spangelo: Well, I mean, SWARM certainly wants to focus on our short term goals of putting up these 150 satellites. We also have aspirations of future constellations and other things that we might do. I’m also becoming very interested and feeling like we’re not doing enough around climate change. That’s something that I personally want to put a lot of effort into over lifetime. I think that’s something that segues probably nicely from some of the SWARM work. But it’s kind of a broad category that I’m particularly interested in exploring, maybe during or after SWARM.

Ed Bernardon: No interest in going back and becoming an astronaut candidate again?

Sara Spangelo: I don’t know, I wonder if that ship has sailed? I think if there’s an opportunity to go up on SpaceX, maybe for a week or something, that’ll be pretty cool. I think the commitment to the next 20 years of your life is a very serious one. I’m not sure. We’ll see what the future holds.

Ed Bernardon: What do you envision for the future transportation in space? When do you think you can take that one-week trip on the SpaceX rocket? When’s that gonna happen?

Sara Spangelo: It’s a great question. I mean, the momentum that SpaceX and some of the other space players are exhibiting is very inspiring, and obviously very enabling for SWARM as well. I think probably in the next five to 10 years, we’ll be able to take that trip. People have already signed up for some of these opportunities for very expensive price points. But in my mind, if wealthy people are willing to fund these trips and it’s better for exploration, then I’m all for it. And it funds some of the R&D.

Ed Bernardon: When do you think we’re going to get to Mars? Do you think SWARM is going to help us get there?

Sara Spangelo: Oh, yeah. SWARM is definitely going to be be fueling the internet of Mars, for sure. It just makes sense because we’re small, easy to deploy, low cost, all those things. It’s hard to say that something will go to Mars, JPL has successfully been sending things to Mars for a while. But I think maybe the start of a human type base might be in 10 years, and then maybe people on Mars in 20 years, so maybe by 2040. It’s a total wild guess.

Ed Bernardon: I was looking online at small satellites – and of course, SWARM shows up at the top – but there was another one on there, very interesting, very futuristic called Breakthrough Starshot, and it’s about these credit card size spacecraft that are going to be driven by a light sail and go at 20% the speed of light. Tell me is that a dream? Do you really think are we going to see that soon?

Sara Spangelo: Yeah, we’ve actually worked with that group, and they’ve asked us about maybe using something SWARM like. I think it’s a bit of a dream but the physics all makes sense. There’s still a lot of technology that needs to be verified.

Ed Bernardon: Autonomous cars have raised all sorts of issues here on Earth. Do you see when we start to travel to space? Do you envision any kind of mobility problems, like we’re talking about now in terms of safety or whatever it might be? Traveling in space or traveling on Mars, mobility in general in space, what are the big problems to solve?

Sara Spangelo: Well, there are many, I think the biggest one is just the fact that you can’t just plop the human on the moon or Mars easily because we don’t have the kind of oxygen and the air that we need to breathe, and the radiation environment can be dangerous as well, as we’ve talked about, and the thermal environment can be not perfect for humans. There’s this pretty cool that we can kind of walk around on most of the earth and be okay, most of the time, and that’s not true in those other environments. So, I think one of the main challenges is just how are we protecting humans from the kind of local environment. And then another big challenge is moving any sort of logistics equipment to that site. So, if you want to take a Jeep to the moon or Mars, it’s going to be very expensive because you have to send it in a rocket, and that’s obviously a very expensive and difficult thing to do. So, I think it begs the question like, “How can we build stuff in situ with 3D printing or using some of the local materials that exist on those those places?” And that becomes really challenging. And then there’s also the issue of, you know, if your car has an issue, you just drive it to the shop and you get whatever replaced, and there won’t be those shops in those environments. So, I think we almost need to develop far more reliable, maybe even simpler types of vehicles in those environments.

Ed Bernardon: Well, tell you what? Now is time for the most fun part of the future car podcast. It’s a section of the podcast we called the rapid fire, where we’re going to ask you a set of questions in rapid succession. Really easy questions, you can answer them in a single line, if you want, you can answer it longer, you can even say pass if you want but usually people don’t say pass. So, you’re ready to go?

Sara Spangelo: Okay, let’s go.

Ed Bernardon: We’re gonna start off with ones related to cars because after all, it is the Future Car podcast. So, what was the first car you ever bought?

Sara Spangelo: I’ve never bought a car.Sara Spangelo: I do have a driver’s license and I drive my boyfriend’s Tesla.

Ed Bernardon: Now, one question we always ask on the Future Car podcast is about your perfect living room on wheels. So, imagine you’re traveling from, say, Boston to New York, five-hour trip. In your living room on wheels, you don’t have to drive, of course, so you can have anything you want, any kind of environment. Describe your perfect living room on wheels for that five-hour trip.

Sara Spangelo: A gym with a peloton, a hot yoga studio, and a place to work.

Ed Bernardon: How would that change if this was a rocket ship taking you to Mars?

Sara Spangelo: Change is zero.

Ed Bernardon: What person, living or not, would you want to spend that five-hour car ride with?

Sara Spangelo: Oh geez, probably my boyfriend. He’s okay.

Ed Bernardon: Now we’re going in a different category here, more general questions, not about cars. What’s your favorite planet besides Earth?

Sara Spangelo: Europa.

Ed Bernardon: End the debate right now. Pluto – planet or not planet?

Sara Spangelo: Not a planet, sadly. Even though it’s in all of my books from being a child, and I actually gave you a moon, not a planet for that book.

Ed Bernardon: I was going to call you on that. Were you testing me or should I let that go?

Sara Spangelo: I was just thinking of my favorite round object in space, and that’s where my mind converged.

Ed Bernardon: Well, there is a lot of chance for life there, that’s what they say. If you had to pick a planet, then what’s your favorite planet? A lot of pressure.

Sara Spangelo: Maybe Mars.

Ed Bernardon: Well, what’s your favorite TV show?

Sara Spangelo: Away.

Ed Bernardon: What do you wish you were better at?

Sara Spangelo: A lot of things. Multitasking, even though I’m very good at it but I wish I could do more things at once.

Ed Bernardon: If you hadn’t become a satellite engineer, what would you have liked to have done professionally?

Ed Bernardon: Greatest talent not related to anything you do at work?

Sara Spangelo: Flying.

Sara Spangelo: Therapist. My job is actually to be a therapist, I’ve realized. So, I wish I had more professional training in that.

Ed Bernardon: If you could un-invent one thing, what would it be?

Sara Spangelo: Cellphones.

Ed Bernardon: If you could magically invent one thing, what would it be?

Sara Spangelo: Time travel.

Ed Bernardon: So, the number one company on the most innovative companies was SpaceX. So, on my next interview, once I interview Elon Musk, and I ask him a question that he has to answer, what question would you like me to ask him?

Sara Spangelo: What is the biggest challenge you see with his kind of vision or goal of going to Mars?

Ed Bernardon: This is the last question, once SWARM achieves full global connectivity and a bit more bandwidth, do you think it might be possible that SWARM and the future car podcast can partner to deliver the first live podcast broadcast to reach all corners of the globe?

Sara Spangelo: I would love to support that. I think it’s gonna be a while until we can do voice, we can certainly tweet it if that’s what you’d like to do.

Ed Bernardon: All right, Sarah, thank you so much for taking all this time with us. It was a very interesting interview and I had a great time.

Sara Spangelo: Thank you. Me too. I really appreciate you guys. Bye for now.