The Reach of Your CAD Tools

Solid Edge has always had a great reputation for drawings and sheet metal. Even in my days stumping for competitive products, we always respected the advantages users said that they found in Solid Edge.

Solid Edge has always had a great reputation for drawings and sheet metal. Even in my days stumping for competitive products, we always respected the advantages users said that they found in Solid Edge.

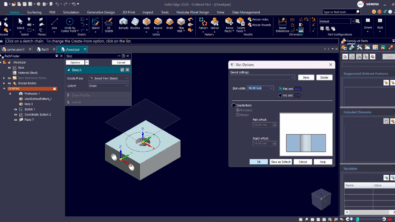

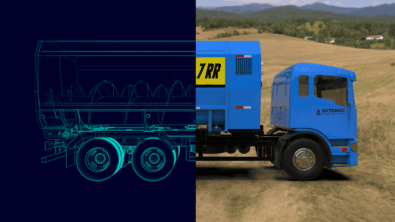

With an accepted advantage in those areas, it makes sense that Solid Edge has gone on to focus on machine design applications.The product is very well suited to machine design, but where do you draw the line in a search for perfection? If you look at the product, the development team has done a great job of building other functions around the machine design theme, such as frames, wiring, piping, and of course all of the 2D documentation requirements that come from machine component manufacturers. You can’t really argue with the success Solid Edge has had in the machine design space. We are still maybe not a dominant force in the market, but the product itself is a compelling piece of design on its own.

The term “one trick pony” clearly doesn’t apply to Solid Edge pursuing perfection in the machine design space, since in order to be good at one area of mechanical design, you have to be good at many areas. Mechanical design is clearly a multi-faceted discipline, where you can’t get by just by being good at one thing, no matter how good you are at it.

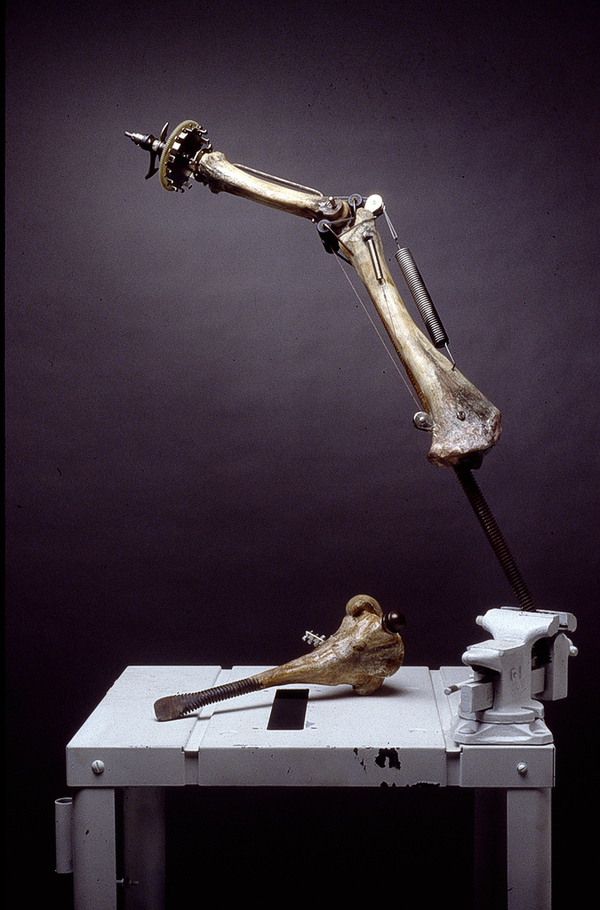

Machine products interface with all sorts of other products. For example, you might use a machine for the automated assembly of consumer products. Or a portion of your machine might require aesthetic components, such as a cover, or some organic shape for a human interface device. More and more, engineered components have organic shapes to optimize 3 dimensional stresses, or to produce shapes that can move efficiently through fluid flow.

So organic shapes really can be a part of machine design. To me this is important, because to be considered a well-rounded product in the market, you have to be able to do more than any single application will require of you. Maybe no single industry will use ever single tool available in Solid Edge, but to have the tools to keep up with all the possibilities, the software may need to have some tools that don’t get used every day.

One of the greatest innovations in the machine design realm is Synchronous Technology. I’ve been a big fan of this for several years, even before I came to work for Solid Edge. “Selection-based design intent” is a big evolution that improves on the typical history-based design which uses what I call “crystal ball design intent”. You make your design intent when you need it, and it always serves your needs, not its own.

So why can’t we push this concept a little. Synchronous Technology is a great concept. And organic shapes are a necessary part of real world design, even machine design. We’ve been able to merge machine design and Synchronous Technology well. The configuration of that merge has evolved over the 7 years since its introduction, but it has constantly evolved in the right direction – always easier to use, always more powerful, always more relevant to its application to real-world design and modeling situations.

Part of the complaint against organic shapes is that they are just too hard to set up with complex curves in multiple directions. Applying a little of the Synchronous Technology to the organic world would mean that we could make better use of organic shapes as necessary. It would even start to open up a little of the consumer product type capability while simply rounding out a complete set of tools for machine design.

What if organic shapes could be created by just clicking on a point on a flat face, and moving that point around to create a bulge or an indentation? What if we applied the concepts of Synchronous Technology that we have perfected in machine design applications to the world of organic shapes to allow us to change a shape without having prepared for that in our “crystal ball design intent” method, with process-heavy pre-established meshes of complex curves?

If you’ve never worked with much surfacing or organic shapes, it compounds the complexity of the shape on top of the complexity of the history-based process. Removing all of that could allow organic shape creation to truly be as intuitive as pushing clay with your thumbs. If you can visualize it in your mind, you can transfer it to your CAD model. It would mean that you don’t have to waste so much brain power on how to run the CAD tool, and use it where you need it – think about the process of design rather than the process of CAD modeling.

Where could you go if your CAD tools could reach just that much further?

Comments