The internet runs on Lava Lamps

Encryption underpins the security of the internet. Encryption requires not only randomness but unpredictability (something that’s really difficult for a computer to generate on its own). Chaotic fluid dynamics systems are a great source of both. Even though you might not have realised it, Lava Lamps and their extremely high entropy levels form the basis of internet security today. How might one model such a chaotic molten wax based system, could Simcenter attempt to ‘break the code’, and why might that ultimately be a fruitless endeavour?

15 Years to Develop

Edward Craven Walker, an accountant and former RAF pilot, after seeing an egg-timer device made from 2 immiscible liquids in a country pub in Dorset UK, spent the next 15 years refining the design of what would come to be known as the Lava Lamp. By 1963 he had perfected the design and commercialised the ‘Astro Lamp’. Just in time for the swinging ’60s and as Walker commented: “If you buy my lamps, you won’t need drugs”.

A Perfectly Poised Fluid Dynamics System

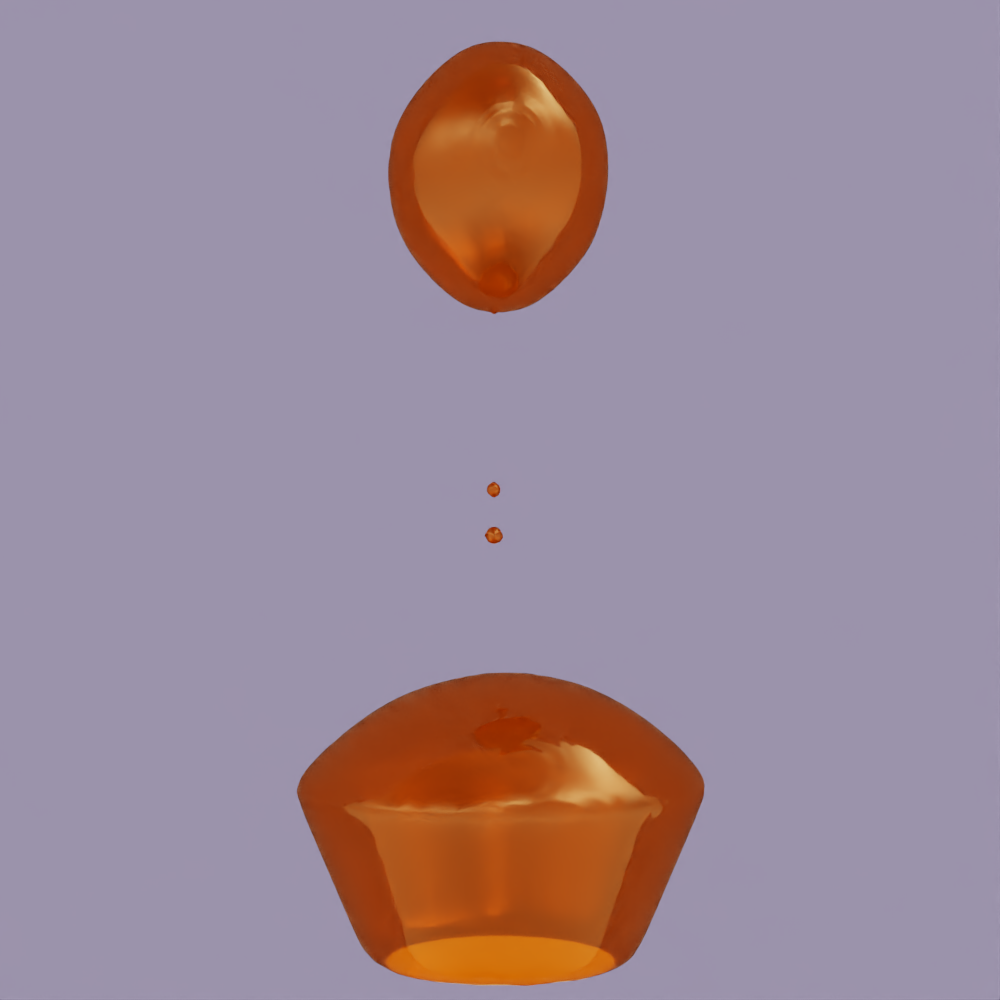

A bulb acts as a heat source at the bottom of the glass that heats the wax to the extent where its density decreases enough (by no more than 1% less than the density of water that it sits in) so that globules of wax will rise due to buoyancy, cool as they move up away from the lamp heat source, so ultimately fall back down again as their cooled density becomes greater than the water in which they float.

Too much heat and resulting higher temperatures would then see the wax float to the top of the lamp and stay there for ages. Too little heat and then the wax wouldn’t ‘globulate’* upwards. Somewhere in between and you get this beautiful delicate balance between buoyancy, viscosity, density and surface tension.

[*‘Globulate’ – not a recognised term, but nevertheless one that serves well when applied to Lava Lamps!]

What on Earth has this got to do with Internet Security?

Secure Shell (SSH) is a protocol that lets you safely connect to and control remote machines (amongst other things) over an otherwise insecure network. It creates an encrypted channel between you and the server, ensuring that anything you type or transfer can’t be read or tampered with by others.

SSH keys act as your cryptographic identity: one public key sits on the server, while your private key stays with you. When you connect, the server challenges your private key to prove who you are – without ever revealing the key itself – creating a secure, trusted link.

SSH keys are created by feeding a source of high-quality entropy into a cryptographic key-generation algorithm. That entropy seeds a random number generator, which produces the large, unpredictable prime numbers and bit patterns that form the private key; the public key is then mathematically derived from it.

In this context, entropy means the amount of true, irreducible unpredictability feeding a random number generator. It is derived from physical irregularities: timing noise, thermal fluctuations, chaotic motion, ensuring that the bits used to create an SSH key are impossible for an attacker to guess or reproduce.

The transient behaviour of lava lamps is a rich source of entropy. Their motion is chaotic, sensitive to initial conditions, and exhibits a positive Lyapunov exponent, a hallmark of systems where tiny uncertainties grow exponentially over time. This makes them effectively impossible to simulate or predict with meaningful accuracy.

The Wall of Entropy

The need for high-quality entropy in cryptography became obvious after the Netscape vulnerability of 1996, when researchers discovered that Netscape’s SSL keys were generated from only a few predictable values: the system time and process IDs. With so little real randomness, attackers could recreate “secure” keys and break encrypted sessions. That failure cemented a simple truth: cryptography collapses the moment entropy becomes predictable. In response, SGI (Silicon Graphics, Inc.) developed LavaRand, an early system that generated entropy by photographing a cluster of lava lamps and hashing the resulting pixel data – recognising that the chaotic, fluid behaviour inside those lamps produced far richer unpredictability than any software-only approach.

Cloudflare later revived and expanded this idea across its global offices. At their San Francisco headquarters, a camera continuously photographs a wall of lava lamps, feeding their shifting colours and wax blobs through a cryptographic hash function to extract entropy. In London, the company uses a double pendulum, whose chaotic motion is impossible to predict over time, and in Singapore they rely on the random timing of radioactive decay from a safe isotope source. All of these signals – lava lamps, pendulum, and atomic noise – are hashed and mixed into Cloudflare’s entropy pool, helping to seed the cryptography protecting a significant share of global internet traffic.

HaeB, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Simulation is not always Prediction

Of course, you can simulate physical phenomena, very accurately in most engineering contexts. For the vast majority of applications, simulation and experiment agree closely, and this is well established. But when you look at explicit, non–time-averaged transient behaviour in genuinely chaotic systems, such as turbulent eddies or motion inside a lava lamp, the situation is different. You can absolutely simulate the physics, but you cannot expect the simulation to reproduce the exact time-evolving signal of a specific physical twin. Even tiny uncertainties, microscopic temperature differences, minute variations in geometry or material properties, cause the real system and the simulated one to diverge over time.

This isn’t a limitation of the simulation software; it’s a fundamental property of nonlinear dynamical systems. Chaotic regimes exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions, the so-called butterfly effect, governed mathematically by positive Lyapunov exponents. In practice, this means the transient details will always differ, even though the derived, time-averaged engineering quantities remain accurate and highly useful. Chaotic systems can be simulated, but not predicted in their exact instantaneous evolution.

It is exactly this chaotic ‘non-predictable’ behaviour that underpins the high entropy conception on which the ‘Wall of Entropy’ is based.

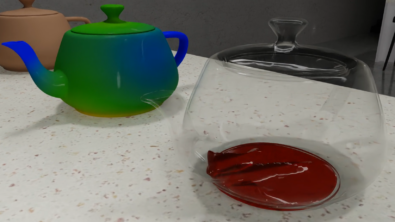

Simcenter can model what ever you might throw at it

I used Simcenter to simulate the Lava Lamp. Considering that it took 15 years for Edward Craven Walker to derive the perfect wax properties, and that it is rumoured that only 6 people in the world today know the exact constituents of the augmented wax material, my challenge was not so much in the simulation numerics (Simcenter ate this for breakfast) but to try to reverse engineer the wax material properties so as to replicate a typical Lava Lamp ‘globurised’ transient flow.

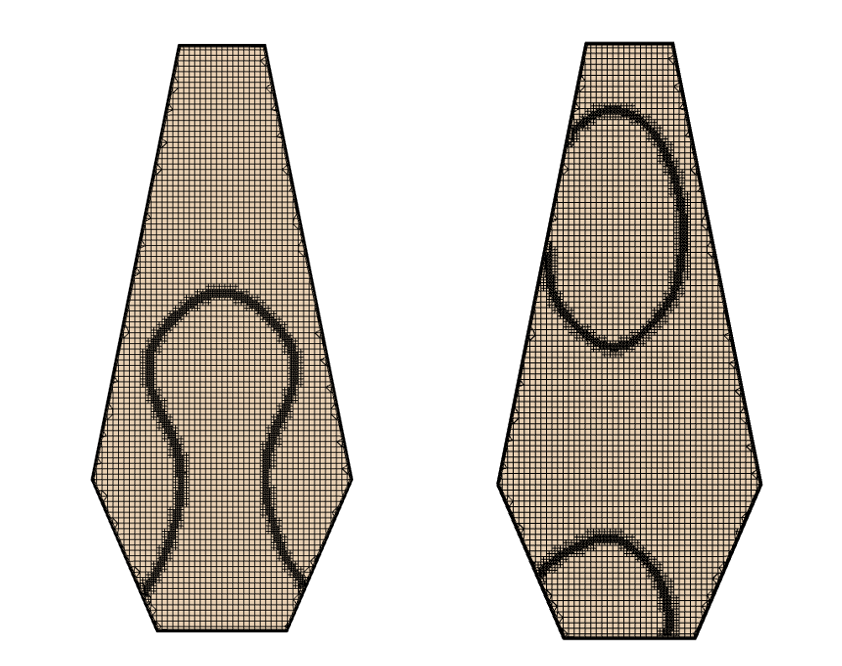

The time step by time step adaptive mesh refinement in Simcenter enabled the immiscible interface between wax and water to captured directly. The real challenge though was to identify the wax material properties in terms of temperature dependent density and viscosity and its surface tension. In addition the wettability nature of the wax/glass lamp interface and the heating power necessary to ensure the wax doesn’t heat up too much, or too little.

A devilishly challenging CFD simulation. Given more time I might have more accurately reverse engineered the wax material properties that are the preserve of those 6 people. As it is I achieved some level of globurisation and at the very least it exhibited the chaotic behaviour that is relied upon to secure the internet data transactions of today.