Toast happens: A Friday the 13th special

A historical bite of toast, butter and marmalade

The concept of “toasting” bread, or heating it over a fire, is incredibly ancient. Its primary purpose is crucial for preservation and making bread more palatable when fresh options aren’t available. In Ancient Egypt, bread was a fundamental part of life, but the warm, arid climate meant fresh bread spoiled rapidly. To combat this, Egyptians ingeniously developed methods to extend its shelf life, often re-heating or extensively drying it out over a fire. This process, essentially an early form of toasting, removed moisture, significantly inhibiting mold growth and spoilage, ensuring a consistent food supply.

The Romans were particularly fond of “tostum,” a Latin term from which our modern word “toast” directly derives, meaning “to burn,” “scorch,” or “dry by heat.” For them, toasting was an essential method to salvage stale bread and make it edible again. Roman soldiers, in particular, relied heavily on toasted bread as a durable and lightweight ration during their long campaigns, as it was far less likely to mold or spoil than fresh bread. To soften and flavor this hardened bread, Romans would often dip it in wine, olive oil, or even broths, transforming a simple preservation technique into a more satisfying meal.

The pairing of toast with butter became more widespread from the 16th to 18th centuries as dairy production improved, establishing it as a recognized breakfast item. Finally, marmalade and jams gained traction in the 18th and 19th centuries, with bitter orange marmalade famously commercialized in 18th-century Scotland. This evolution transformed toast from a practical necessity into the beloved breakfast staple we know today, and raised the question: Why does toast always fall buttered-side-down?

The toast falling simulation model

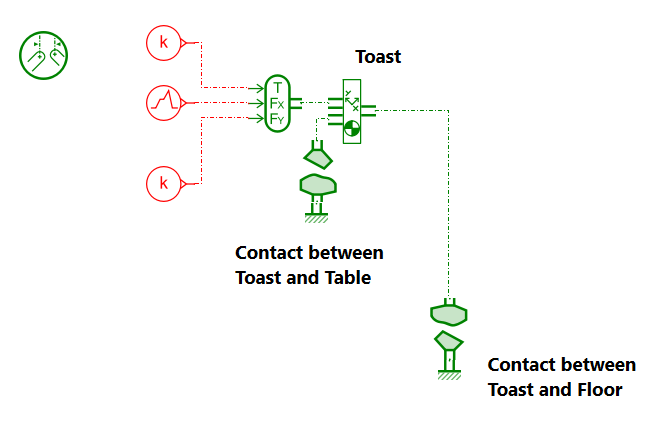

In this project, we developed a simple model using Simcenter Amesim software to analyze the interactions within a basic 2D mechanical system. The model focuses on the contact between a table and a piece of toast, as well as between the toast and the floor. We assume that the toast begins to fall when a small force is applied outward, in the direction away from the table, along the edge of the toast parallel to the table’s edge. More complex models could be developed to account for different orientations of the toast on the table; however, for this analysis, we adopt the simplest approach to ensure ease of understanding and clarity.

To explore different scenarios and understand the system’s behavior under varying conditions, the model includes parameters such as the applied force along the movement axis and the height of the table. By adjusting these two parameters, we can simulate and analyze how the toast responds during movement and potential impacts.

Boundary conditions leading to unlucky outcomes

When studying the boundary conditions that cause a piece of toast to fall off a table, based on my own experience, it usually happens when we accidentally bump the toast with our hand or elbow while turning around, meaning the applied force is generally quite small. Additionally, the toast typically rests on a table or kitchen countertop, where the height of such furniture ranges from 70 to 100 cm.

In this study, we performed a batch run consisting of 21 trials, varying the initial force and the height of the table to observe their effects on the results.

Analysis of a predicted toast tragedy

To analyze the results, we created a relationship map with the difference in table height on the x-axis and the variation in initial force on the y-axis. Red dots represent cases where the toast falls buttered side down, while blue dots indicate those where it falls buttered side up.

When the toast is accidentally nudged off the table, the initial force pushing it outward is usually small, resulting in a low horizontal velocity (x-axis). This generates a low parabolic trajectory with a vertical gravitational force (y-axis) acting downward. The combination of these forces produces enough torque to cause the toast to flip partially while falling. However, because the table height is generally low, the toast has limited time to rotate, typically completing only about half a turn and landing buttered side down.

Similarly, if the force pushing the toast outward from the table is too strong, the horizontal (x-axis) force becomes greater than the vertical gravitational (y-axis) component, and the toast does not generate enough torque to flip over. However, having a very tall table or a combination of both factors can give the toast enough time and angular momentum to complete a full flip and land buttered side up as well.

Toasting up some serious simulations

As mentioned at the beginning, this is a simple analysis of toast falling from the table. We could also create a more complex simulation by modeling the system in 3D and considering different angular positions of the toast on the table, not neceseraly paralel to the edge of the table. Additionally, we could vary the stiffness of the toast depending on the degree of toasting. Instead of running a batch simulation, we could perform a Design of Experiments (DOE) directly in Simcenter Amesim or connect Simcenter Amesim with Simcenter HEEDS for more advanced analysis.

Butter side down: blame physics not Friday the 13th

Today is Friday the 13th, and if your toast happens to fall buttered side down, don’t immediately blame bad luck. Maybe, just maybe, it’s not a curse or superstition at play—but a simple matter of physics. Gravity, angular momentum, the height of your table, and even the stiffness of the toast all team up to decide how your breakfast lands. So next time you see that buttery disaster on the floor, remember: it’s science, not superstition, that’s making your morning a little messier!