Simulation and the Industrial Metaverse

The Industrial Metaverse (IMV) does not yet exist, not like the Internet does. Since its foundations in the 1960s, through its rapid rise in the 1990s, the Internet today is pervasive. The IMV finds itself today in the same position as the Internet did 50 years ago. Its potential is clear, as are its requirements, especially when it comes to the role of realistically mirroring physical behavior, i.e. simulation. Similar to the internet, we expect its first use in research and industrial settings before it hits the broad masses.

This blog explores how simulation technologies – from high-fidelity physics solvers to real-time interactive models – are paving the way for the IMV. Drawing comparisons with the early Internet, we examine where we are today, what challenges remain, and how technologies like GPU acceleration, reduced-order modeling, and visual realism are shaping this emerging digital landscape. In this blog post we specifically connect the vision of the IMV to our own past work. While the term IMV was coined only recently, we have been working towards this vision for large parts of our careers.

From Then Until Now

The term ‘Metaverse’ was coined by author Neal Stephenson in his 1992 science fiction novel ‘Snow Crash’. In the book, the Metaverse is a fully immersive virtual reality space where people, represented by avatars, interact in a shared digital world.

Though one might conceive of different types of Metaverse, e.g. Commercial, Social, Industrial, there is a common underlying definition that forms their requirements:

‘Realism’ will play a central role. Real in that a Metaverse is a reflection, a mirror, of reality. Reality is founded on a collection of physical phenomena. One of those, though not the only one, is optics.

From Visually Compelling to Completely Compelling

Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) has come a long way since the film Tron pioneered such effects in 1982 and Jurassic Park took it to the next level in 1993. To achieve ‘photo-realism’, CGI is in effect just an optical simulator. That one technology simulates that one physical phenomenon extremely well. Here a personal favourite from 2022, the first time we really couldn’t distinguish CGI from reality, using Unreal Engine 5 and lit with Lumen:

2022: Photo-realistic rendering in Unreal Engine 5 (source)

Was it rendered in real-time? No. About 7 frames per second was the rendering rate but it’s a ‘when, not if’ we should see such capabilities in the future, enabled by the ongoing acceleration of GPU hardware technologies.

Optical simulation is only one piece of the puzzle – we also need to simulate how things heat up, vibrate, flow, and sound. Realism isn’t just photo-realism, what’s needed is a complete simulation of all relevant physical phenomena and, to achieve interactivity, this should be achieved in real-time (or even faster than real-time).

From Particles to Fields

Physical phenomena simulation can broadly be grouped into four areas:

- Discrete vs. Continuum, where discrete methods like DEM and molecular dynamics model individual particles or entities, while continuum methods like CFD and FEA treat matter as continuous fields governed by partial differential equations.

- Physical Domains, covering mechanical (e.g. structural stress), fluid (e.g. airflow), thermal, electromagnetic, and acoustics.

- Numerical Methods, such as FEM, FVM, FDM, BEM, SPH, and LBM, each suited to different types of domains and geometries.

- Scale, ranging from macroscopic (e.g. vehicle aerodynamics) to mesoscopic (e.g. granular media) to microscopic (e.g. molecular or even atomic interactions).

The combination of each, for a given simulation use-case, will dictate the balance between predictive accuracy and simulation speed. To satisfy the ‘interactive’ requirements of the IMV, where there is a real-time link between the 3D world, how a user interacts with it and how the 3D scene also interacts with itself, some simulation approaches are better suited than others.

Discrete approaches such as DEM are already well suited. Similarly particle-based approaches for continuum-mechanics such as Computational Fluid Dynamics are also well suited. Albeit they achieve only a limited accuracy when stripped down to achieve interactive behavior, they are useful for many applications, e.g., prediction the evolution of smoke in buildings during early design phases as we have demonstrated in a small demo back in 2018:

2018: Interactive Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics in Virtual Reality (source)

However, when it comes to full order model 3D Field simulation, to reach an acceptable predictive accuracy often incurs a penalty in terms of the required number of vertices (FEA) or control volumes (FVM) to resolve the field gradients. This in turn prolongs the solution time, taking it far away from any consideration of the Metaverse requirement for real-time interactivity. Despite this, the photo-realistic aspects of a Metaverse are well suited for CAE post-processing…

From CAE Post-processing to Real-time Interactivity

A sun-up to sun-down diurnal thermal simulation of a yacht is no small feat. The solution time is measured in hours due to the geometric complexity, the sheer number of control volumes that are required to capture that complexity and the number of time steps required to resolve how the resulting solar loading effects the resulting surface temperatures throughout the day on the occupied portion of the top deck. Modelled in Simcenter STAR-CCM+, the resulting transient results are post-processed and rendered out in Omniverse. In addition a bespoke heads-up display is included to indicate relevant KPIs so that stakeholders in either the design, or purchasing, of the yacht can be appraised of its thermal behaviour (with and without awnings):

2023: Interactive Post-Processing in Omniverse (source) – courtesy of Princess Yachts

A good example of the combination of both the optical physics (left side) and thermal physics (right side).

Although satisfying the ‘physics-realistic’ Metaverse requirement, it falls far short of any level of interactivity. So the challenge is to maintain the predictive accuracy of a full-order CAE simulation model, but enable a model to be fast enough to solve to the extent where it can be interacted with.

Model order reduction is an approach by which a full-order model (FOM) can be converted into a reduced-order model (ROM), whilst not compromising on accuracy. Various methods exist to achieve this, but here’s one example from 2024 using Simcenter Flotherm’s unique ‘BCI-ROM‘ capability. A ROM of an inverter is extracted, accommodated in an Omniverse scene where a heads-up-display allows for real-time control of the power dissipation in the IGBT and Diode chips. The resulting thermal response is reflected in real-time:

2024: Interactive thermal Reduced Order Model in Omniverse (source)

However, it still takes time to extract the BCI-ROM a-priori so real-time interaction can only be achieved after this initial extraction time penalty.

But simulation capabilities are developing rapidly and very soon we will see full interactive computational tools of industrial quality in the IMV. We have been developing towards this for a number of years now, starting back in 2011. While we are not there yet commercially, several spin offs such as the NX Performance Predictor have emerged in the past:

2011: Interactive Computational Fluid Dynamics (Lattice Boltzmann) on GPUs (source)

2017: Interactive Finite Elements in Virtual Reality (source)

From Simulation to Shared Experience

One of the defining characteristics of the IMV is its capacity to host multiple users in a shared, persistent virtual space. This immersion goes beyond visual realism – it’s about presence, where geographically dispersed teams can collaborate in real time, interacting with digital twins as if they were physical objects.

Engineers can walk through virtual factories, designers can iterate on prototypes together, and stakeholders can assess performance metrics from within the simulated environment. This collaborative space not only shortens feedback loops but also enhances understanding, alignment, and decision-making across domains. The value lies not just in the simulation itself, but in the shared experience of simulation, where human intuition and digital precision converge.

2016: Collaborative Systems Design in VR

2019: Collaborative Concept Design in VR (source)

From Design to Deployment

While the design phase of a product often relies on digital twins without physical counterparts, manufacturing and operational stages present unique opportunities for the IMV to enhance real-time decision-making and efficiency. In these phases, the convergence of physical assets with their digital twins becomes more central, enabling a more dynamic and responsive system.

Manufacturing: Bridging the Physical and Digital

In the manufacturing stage, digital twins can be synchronized with physical production lines to monitor processes, predict maintenance needs, and optimize performance. By integrating sensor data with simulation models, manufacturers can create a feedback loop that allows for continuous improvement and rapid response to issues.

In-Operation: Real-time Insights and Adaptation

Once a product is deployed in operation, the IMV would facilitate ongoing interaction between the physical asset and its digital twin. Technologies such as virtual sensors and Kalman filtering come into play here. Virtual sensors estimate unmeasurable states by combining limited physical sensor data with predictive models, while Kalman filters continuously update these estimates resolving the contradiction between deterministic simulation models and the stochastic nature of reality.

This integration allows for:

- Predictive Maintenance: Anticipating failures before they occur, reducing downtime.

- Performance Optimization: Adjusting operations dynamically for efficiency.

- Adaptive Control: Modifying system behavior in response to changing conditions.

Siemens’ Simcenter 3D Smart Virtual Sensing utilizes Kalman filters to merge measurement and simulation data, providing a comprehensive view of system behavior. Here the Executable Digital Twin (xDT) enables real-time simulation on edge devices, allowing for immediate insights and control adjustments.

Examples we have pioneered are for example the overlay of interactive simulations on real hardware devices, e.g., back in 2018 on an electric motor:

2018: Executable Digital Twin of an electric motor (source)

and here a real-time simulation model of a turbine blade undergoing deformation:

2022: Executable Digital Twin of a wind turbine blade (source)

From Now Until Then

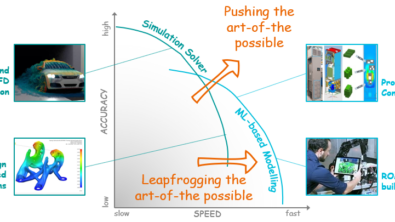

The roadmap that will govern the adoption of industrial strength simulation into the IMV is predicated on the following schematic that relates simulation time (from off-line to interactive) and predictive accuracy:

This Pareto front can be pushed out either by an acceleration of existing full-order model approaches, or via accommodation of more novel approaches such as ROMs, ML or hybrid methods. Whereas the former will be constrained by hardware compute roadmaps, the latter can take advantage of as yet untapped algorithmic innovations.

From a physical phenomena perspective, we are years away from simulation technology being able to reflect, in real-time, the behaviour of any xDT that exists within a virtual 3D world, any interaction with it and all relevant physics associated with that, to a usefully accurate level for industrial application. But just like Rome and the Internet, it won’t be built in a day. It will be approached through a series of technology innovations, be they in software or hardware.

As simulation and hardware technology evolve, the line between real and virtual will continue to blur. The Industrial Metaverse will be built not just on digital twins, but on trustworthy, interactive simulation. Whether you’re in design, operations, or strategy – now is the time to start preparing for this digital leap.

Disclaimer

This is a research exploration by the Simcenter Technology Innovation team. Our mission: to explore new technologies, to seek out new applications for simulation, and boldly demonstrate the art of the possible where no one has gone before. Therefore, this blog represents only potential product innovations and does not constitute a commitment for delivery. Questions? Contact us at Simcenter_ti.sisw@siemens.com.