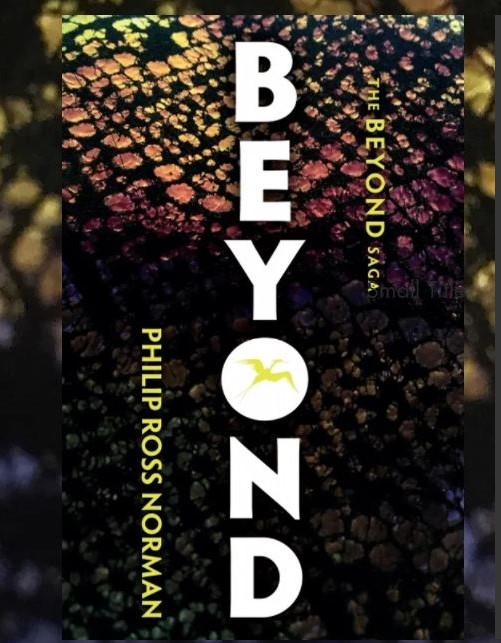

New Young Adult Novel Casts Children as Guardians of a Sustainable Future

An interview with the author of Beyond

Beyond is the latest in a history of wide-ranging accomplishments for Philip Ross Norman. We first met Philip in his role as a co-founder of Ross Robotics, a UK company specializing in modular robotics. Philip is a serial inventor and accomplished entrepreneur. Before robotics, he lived in France where he had his own architecture and landscape design company. He has also worked as a caricaturist for several magazines and most of the national UK papers, authored and illustrated several children’s books, and exhibited and sold many paintings and graphics. Philip has a degree in English literature from Cambridge University. He currently resides in the UK.

We are excited to share news of Beyond with educators and students in our community because the book brings together so many important and intersecting themes around technology, innovation, and social responsibility.

Q: Philip, Congratulations on the recent release of Beyond. Can you summarize the story for our readers?

Beyond is the first installment of a new saga. The story is a dystopian fantasy adventure about an alternative world that is very like our own though radically different in certain ways. It features many exotic creatures (monsters), recognizable characters (kids who go to realistically dreadful schools or kids growing up in an orphanage), and extremely advanced technology. All these elements combine with ancient magic and mysterious prophecies to produce an experience that feels contemporary and familiar but is also time-shifty and unfamiliar.

The essential theme is the eternal struggle between good and evil with hero-type characters making perilous journeys and performing great deeds, though, true to the haphazardness of life, often not knowing that that is what they are doing. The action moves from the futuristic City to the deep and treacherous Beyond across the almost impassable Chasm. This is a natural geological gulf that divides the safe, controlled and knowable world from the phantasmagoric, nightmarish world of our worst imaginings. The princess Zaera, fleeing the Beyond and her wicked uncle, loses the fabulous stone, the Tyra, to her shadowy adversaries – adversaries so shadowy that she doesn’t actually know who they are, the State or the tech. companies clearly usurping the power of the State or the warlords running amok in the Beyond? She needs help to recover this ancient talisman and unleash its awesome power against the forces of evil.

Help from who though?

This is where the unsuspecting children, living in the depths of the forest, come in, also their despised counterparts, the City kids who zoom around in their spoilt-brat flying machines (Autoglyptors) gifted to them by plutocrat, neglectful parents. Such unlikely allies, but when your world is being destroyed, even your enemies can become your friends. But will they win out? Can they survive the onslaught of modern, technological powers so great that maybe even the most ancient, magical powers from the distant past are helpless?

Q: What inspired you to write Beyond?

I was watching the news coverage of the bombing of innocent civilians in Syria. And I recall one family, with two young girls who were going to ballet classes. The mother and father were both professionals, so this family was leading a life not unlike that of many in the West until the world around them went mad. They found themselves in an inflatable boat, fleeing their country. My reflection was, this could happen to any of us. In Beyond, terrible things happen to people who would never have guessed that such a thing was possible. And in the real world, we are seeing history repeat itself.

Q: You’ve been a successful architect, artist, inventor, and now author. It might be easy to conclude that you are inherently creative, but I’m guessing there is more to it than that. Are there certain attributes that you have cultivated that enable you to succeed is so many different fields?

Nothing that I would recommend! However stubbornness has helped – my clarinet teacher always thought that I had little talent for the clarinet but by sheer perseverance, I progressed, did the music exams etc., and somehow managed to play the clarinet in orchestras and bands without getting shouted at.

Otherwise, fear of boredom is quite high up the list, as the moment the threat of boredom looms I feel the need to make life interesting in some way. One of the most effective ways, as it doesn’t involve too many variables that I can’t control, is to create something.

In terms of creativity, I think that trying to look at things in a way in which they haven’t been looked at before can help, it’s a little bit akin to asking a silly question or being intentionally annoying and provocative and seeing what happens. One of my favorite fictional characters is Donkey, in Shrek. One of my patented inventions, a biomimetic traction system used on robots, is called CLAWWS™, mainly to be annoying but memorable too.

Q: Do you remember when and how you first discovered your creative ability or passion? Is there anything in particular that helped you to make that discovery that might help others to discover their own talents, creative or otherwise?

I started making drawings when I was very small. They were extremely long things, lots of A4 sheets joined together with sellotape; the first ones were monorail and cable-rail train lines seen in 2D with all the wires and rails and trains suspended, platforms, and so on. There was a kind of narrative in this, wordless, of growing complexity as trains approached a city and the lines multiplied, of being carried inexorably into the center of things. This was both a frightening feeling and exulting. My earliest years were spent in central Africa, shoeless and unaware of the modern world. So when at the age of seven I first encountered big Western cities, monorails and cable-rails were the answer.

Also, my family was very uncreative and apparently not that interested in what I was doing, so diving into making these extremely long drawings was a wonderful escape into another world, one that could extend and extend simply by using sellotape. I don’t think I can say anything helpful for others about discovering their own talents other than whatever feels important enough that it keeps coming back, find out what it is and explore.

Q: What challenges have you encountered in pursuing your passion early on, and how did you overcome them?

The earliest challenge was sub-contracting the drawing of the monorails. At school, I recruited drafts-people – fellow pupils – who developed the basic idea into a full-blown illustration after I’d sketched out the cables and tracks (I finished some sections so they could see what was required). Not much later it was perfectionism: until something was right it was wrong and that bothered me inordinately. When I was a full-time caricaturist on newspapers and magazines I had tight deadlines to meet but was often very dissatisfied with the result. The biker who had come to collect a drawing would be sitting in the kitchen with his huge boots up on the table, smoking, as this was a time before smoking was very frowned upon. I would be fretting in an adjoining room about, say, President Reagan’s nose, or the particular set of his eyes: was it a likeness, did it express something interesting and real about him? Whereas, all the biker wanted was the drawing so that he could deliver it and get paid.

So the takeaway: very early on the raw creative impulse bumps into the harsh realities of the everyday world. The challenge is to not lose the original impulse.

Q: Have you experienced any failures along the way and how did they influence your career?

Far more failures than successes. In a proportion of about 1000:1, possibly a lot more. When I was making ceramics a whole kiln blew up destroying everything inside and blasting a deep hole in the concrete floor and nearly killing me, but you only see the pots that worked.

So I’d say, be careful with how you use your energies, as I can see now that I have often been extravagant with how I have used my time. At one point I was building a fish smokery and studying hydrostatic levitation and illustrating children’s books and restoring a barn and doing some teaching in the local schools, and painting, all at the same time. So, focus energies on something, try to plan and to plot, then identify the mainsprings of a new thing, then critique it to a point… but no further, then let go and run with it. And keep at it. In terms of setbacks and how to deal with them, it is a cliché to say that a setback should be looked at as an opportunity because a setback is a setback and it can feel very real and negative at the time. But… time does tend to heal and perspectives do change and with the changing of perspectives ideas evolve, things start to look different. And without being glib, setbacks are perfectly normal, they are like annoyingly persistent grey clouds that keep popping up over the horizon. But each one really is an opportunity. These clouds tend to be silver-lined with some kind of mysterious liquid jostling around inside, freighting them with information. So the thing is to capture them and puncture them… and not complain about the weather.

Q: I imagine that in addition to your natural talents, you’ve also discovered and developed some habits or practices that have helped you to grow as a professional. Could you share those habits and why they are important?

I am far more organized than I used to be, and it makes me shudder to think of how disorganized I was and I still despair at times to see how disorganized I remain. These days I try to compartmentalize decision-making, not considering a certain subject until an appropriate moment arrives. The purpose I suppose is to not get overloaded or even more confused than I already am. And I’ve always been good at a kind of discipline, making sure I work on things rather than dilly dally around. If you’re working from home, an invisible time grid is essential, like, be at your desk and stay there as if you were in an office, well, almost.

However, organizational reform aside, I’ve always kept notebooks and use them in a number of ways. One is in the scavenger mode, vacuuming up useful tidbits that may be reused at some future, unspecified date. If I read a book or an article or something online, or watch television, or hear someone say something interesting (rare), a notebook will always be there, somewhere. Maybe pushed under a sofa or being used as a drinks mat or on the dog’s cushion, chewed.

These notebooks are also used for planning, any kind of planning, writing, painting, technology or another category, other things like say, biplanes. For technology, I’ll do a patent search to see what people have already thought about as this is a vital step to take before plunging too far into a new inventive process – however it is always best to have a few semi-abstract ideas first and only then check to see if anyone else has had similar ones. For writing… the process, if it can be called a process, is more like circling ever more tightly around an idea, crystallizing it by increments, maybe starting with a shaggy-dog story synoptic outline, then trying out some detailed glimpses of events and characters… how they might speak, a description or two, trying to fall little-by-little into a new world until it starts to feel livable and real. All very incremental, as the attendant fear is of getting discouraged and of giving up because the thing won’t come alive, and that’s what you are trying to avoid. But unfortunately, often that’s the case and then it is best to move on, to try something different. Finding the first ideas for Wreckwing, the book I’m currently working on, took about a year with a number of expensive (in terms of time and effort) false starts.

So the notebooks are essential. I now have lots of them, one for inventing, one for my writing and others for technology projects that have nothing to do with robotics. Each is dated and the result is notebooks everywhere. I’ve tried digital solutions but always seem to come back to physical notebooks as the pages can be flicked past rapidly while retaining a sense of where I am, corners can be bent over very satisfyingly, books can be interleaved where two or more things correspond… and often there are interesting marks on the page that function like valuable metadata, reminding me of when and where something was noted down, like a coffee stain or a dead, flattened insect.

More in the technology realm I have had to learn how to work with teams of people, and how to delegate, coming full circle to those early experiments with monorails. Projects of any scale require teamwork and the challenge here is that the creative impulse is generally tied up with a rich vein of individualism whereas collaboration is quite, quite different. So, there is more painful learning and adapting to be done. Which is a recurrent theme.

Q: Generally, what advice would you offer to your own children or other young students about finding their talents and or “dream job”?

My own children are far more adjusted to the world than I am and I wouldn’t dream of giving them any advice.

Looking at all the mistakes I have made I would say, try to latch on to something, even if that means working on it after-hours and even if you have a demanding day job or a very busy study program. Don’t allow things to languish. Anything worth doing needs a lot of doing to make it happen. In an unstructured environment like writing, yes, there are writing courses but there is also nothing like writing and writing and writing, and finishing things, and getting feedback, then writing again. I waited for ages before starting to write at all concertedly, I was thinking that I hadn’t experienced enough life. Then, when I started full-on writing I discovered that I had too much material and I should have started writing sooner.

If what you are interested in has a structured environment that you could learn in, say, you want one day to set up a business in a given sector, go and work for someone in that sector. Most of the learning will happen without you even being aware of it.

Anything worth doing, needs a lot of doing to make it happen.

Q: Do you have any advice or suggestions for educators about how to help students find their passions?

The teachers who most influenced me were the ones that were inherently creative and saw that I was too, so it was a meeting-of-minds even though there was the age difference and the role-play of student and educator. These were very special people who saw no limits, they didn’t focus on exams or schoolwork, they went far beyond that, their references were the anything and the everything that could be relevant. Being believed in by an educator can go a long way because starting out on anything at all ambitious needs a lot of self-belief. And being guided toward potential role models can help too, even if they get superseded along the way. The purpose is to give form to an interest that might evolve into a passion, like being handed the outline of a narrative to follow.

Q: Where can we buy a copy of Beyond?

Beyond is available both as a paperback and as an eBook. For anyone in the United Kingdom, you can purchase a signed copy of the paperback on my author’s website for the same price as an unsigned copy elsewhere. I can’t send the book out internationally as the cost to the purchaser doesn’t make sense.

The publisher’s website gives you links to various online retailers where you’ll find the appropriate format eBook, as well as the paperback. And once you have read it you can post a review of the book!

Thank you Philip for taking time to chat with us about Beyond. I’m already imagining how we might bring the characters to life in Solid Edge Design!

Thank you too. In terms of making things more tangible, I have tried designing some of the technologies found in Beyond, like the Autoglyptors and the robotic dogs, using the hugely powerful CAD tool Solid Edge. But then I ran out of time and have intentionally not put illustrations in the book. It would be very interesting to find out how other people see these machines, and of course the robots.

Join the #SolidEdge conversation

Inspire educators and students to discover the world of engineering by sharing content from Siemens Academic Blog on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn!

To learn more about Solid Edge for Education visit our website.