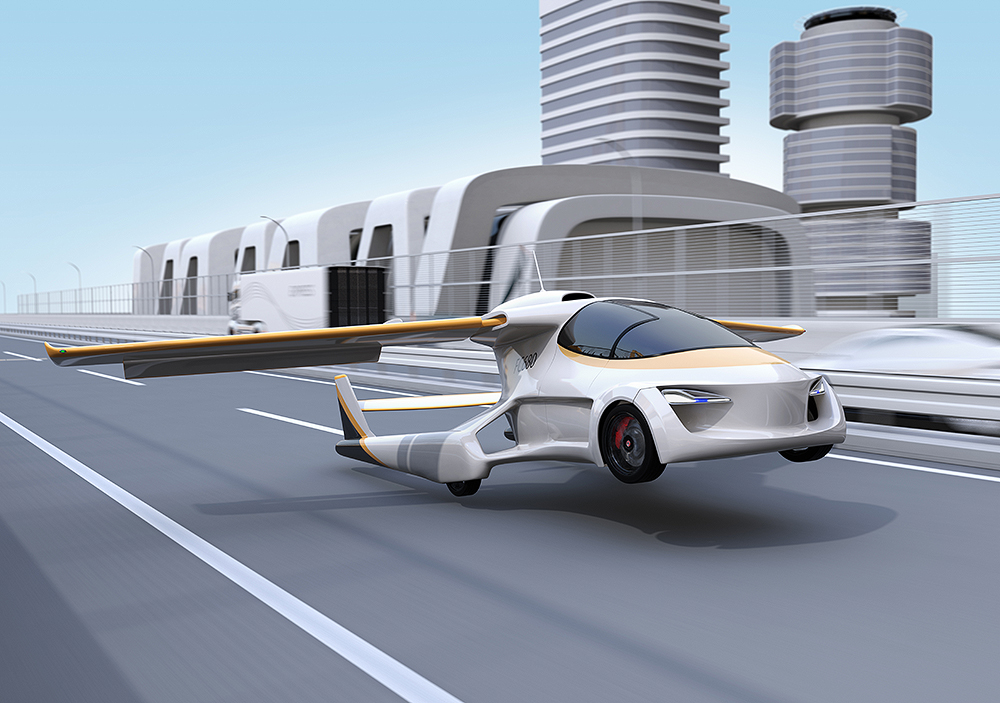

What’s the future for real flying cars?

Increasing urbanization means technologists and thought leaders are looking to the skies for faster, more efficient movement of people and objects.

The race to create new breeds of flying vehicles is on with companies such as Terrafugia, Volocopter, Uber and Airbus already developing them. The concepts range from autonomous vertical-takeoff-and-landing (VTOL) air taxis that whisk busy commuters across town, to personal aerial vehicles, self-piloting cargo and passenger planes, and delivery drones.

While some of these concepts may seem new, early innovators have been toying with the idea of hybrid aerial vehicles for more than a century. In 1917, Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company introduced a car connected to a detachable biplane wing, tail and propeller section. But due to heavy conventional aircraft manufacturing requirements during World War I, the vehicle never flew.

Later in the 1920s, Henry Ford attempted—unsuccessfully—to develop a conventional, folding-wing airplane that was available to the working class. His prediction? “Mark my words. A combination airplane and motorcar is coming. You may smile. But it will come.”

Boston-based Terrafugia has recently made Ford’s prediction a reality. The Transition, a two-seat automotive vehicle and light sport aircraft, has its first deliveries in 2019. The vehicle has folding-wings and a range of 400 miles in the air; on the ground, it will be capable of “highway speeds” and run on premium gasoline.

Companies like Volocopter, UberAir and Airbus are working towards autonomous technologies for self-piloting urban air-mobility vehicles, cargo drones and passenger drones.

Volocopter has partnered with Dubai in the United Arab Emirates on autonomous air taxis. Volocopter’s all-electric 18-rotor VTOL (e-VTOL) took to the skies in 2017 for a five year trial. The taxi will be integrated with other public transport systems, and passengers will be able to book and track flight paths through a smartphone app.

Uber is getting into the game with UberAir, a flight-sharing network that uses autonomous e-VTOLs for urban transport.

Airbus has developed an e-VTOL called CityAirbus. Airbus has also successfully tested drones capable of carrying cargo and passengers. These aircraft employ “sense-and-avoid” technology built on artificial intelligence, and particularly deep learning, to enable the vehicle to understand complex environments and then make decisions.

But autonomous flight still has some major hurdles to overcome, namely federal safety and regulatory frameworks. A major increase of aircraft in the skies will require new systems to manage traffic. Challenges will include how vehicles talk to each other, how they will react to changing weather conditions and how they will recognize no-fly zones, such as airports.

Cybersecurity is also a concern. According to PwC, as organizations rush to develop their technology platforms for autonomous flight, the number of exploitable vulnerabilities will increase.

While these vehicles already exist, Gartner predicts the regulatory environment surrounding them is unlikely to be ready before 2027. Other obstacles to overcome include safety issues, the technology’s high cost, and a lack of critical infrastructure to support such vehicles.

Still, experts are looking to self-driving cars both on the ground and in the air to help lead the way. Automakers are already making major headway for self-driving car technology – and autonomous air flight may end up taking off sooner than expected.

This concludes part two of our series on how flight is changing. In part three, we discuss the future of flight in space aeronautics. If you missed part one, click here to read about the part autonomous drones play in the future of flight.

About the author

John O’Connor is the director of product & market strategy in the Specialized Engineering Software (SES) organization of Siemens PLM Software. SES develops and markets CAD-integrated, specialized engineering software for product design and manufacture in the aerospace, automotive and other design-driven industries. O’Connor has served in numerous roles at Siemens, ranging from application support and technical sales management to business development. Prior to Siemens, he was a senior design engineer at Lockheed Martin, where he led a number of product design teams. He holds a Master of Science in materials engineering and a Bachelor of Science in mechanical engineering.