Digital disruption: the greatest thing since sliced bread

We recently held our annual industry analyst conference in Boston. The conference gives us an opportunity to communicate our vision and strategy to analysts, customers, partners and trade journalists. The theme of the conference was “Realizing the Digital Twin,” and our business segment leaders networked with this group of influencers and emphasize our industry leadership.

This was the first time I’ve had the chance to speak at this event. When I was asked to speak, I said, “Why would the press and the analysts want to hear from the sales guy?”

They convinced me that it would be worthwhile to give my frontline perspective on how our customers’ needs are changing in this era of disruptive innovation and what we’re doing to respond to the changes digital disruption brings to the market.

At first glance, our customers’ motivations haven’t changed all that dramatically. They still want to make the greatest things since sliced bread: especially since it might be digital bread, but the pressure for fast, impactful innovation has never been greater.

While customer’s goals have essentially remained the same, what’s different is that customers are becoming more receptive to thinking beyond the confines of their traditional engineering operations. Sure, they still care about improving their design process, accelerating simulation and squeezing efficiency out of manufacturing. But they’re increasingly looking for something beyond the average domain-to-domain optimization—and considering a more holistic, digital disruption type of approach to the business of innovation.

That’s part of what prompted us at Siemens to develop a similar mindset. Yes, we still work with separate disciplines in our customer base: design organizations, simulation specialists, manufacturing engineers, industrial engineers, MES teams, electronics experts, systems analysts – you name it. But more and more often, the conversations we’re having with our customers are about their overall business, how digital disruption could be used to their advantage, and how we can help them disrupt their industry, or even other industries.

That’s why we’ve been working to show them how weaving a digital thread through their entire innovation lifecycle can transform their business.

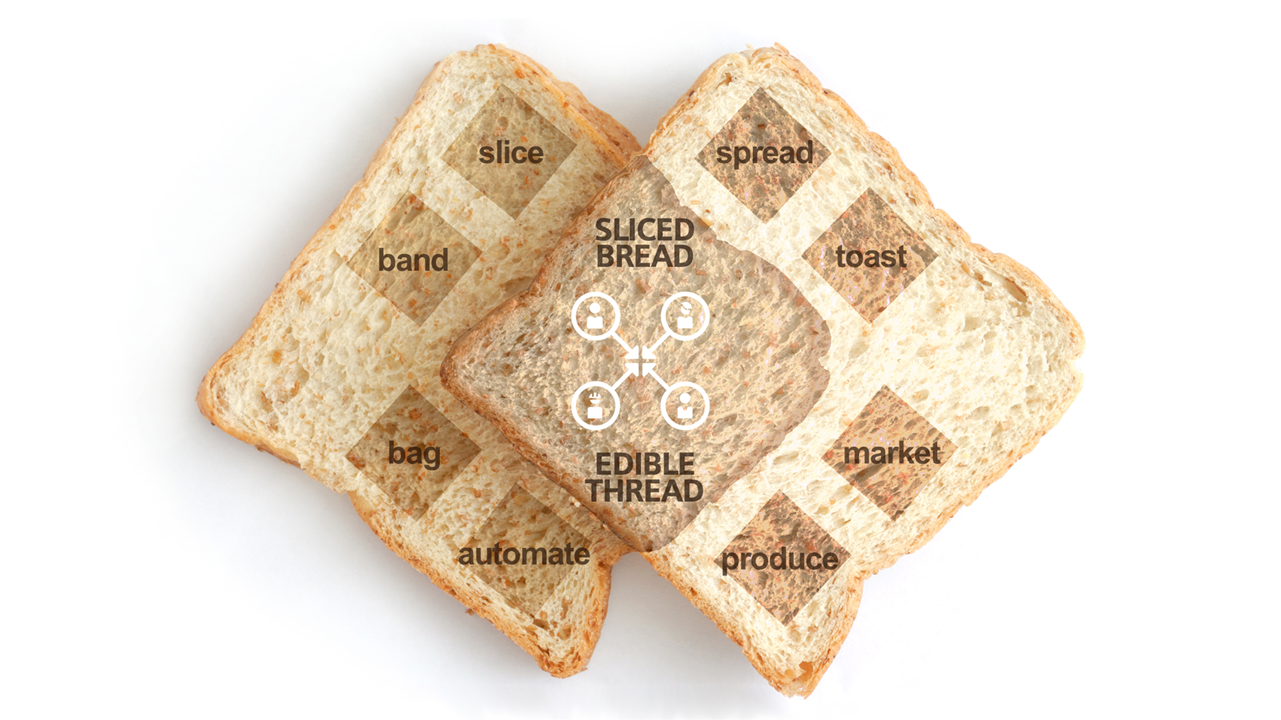

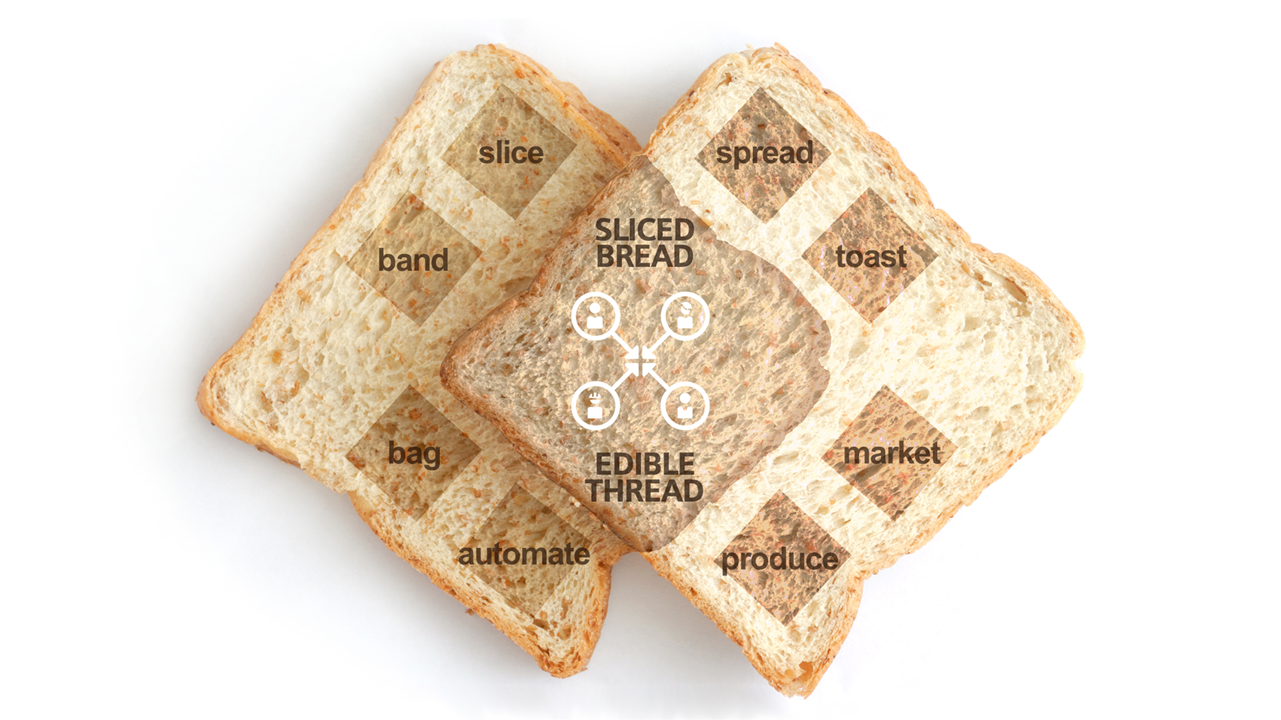

To understand how important a digital thread is throughout a product’s lifecycle, you don’t have to look further than your kitchen.

To understand how important a digital thread is throughout a product’s lifecycle, you don’t have to look further than your kitchen.

Let me give you an example. It starts with a guy named Otto Rohwedder; he actually invented sliced bread. He’s the original disrupter, the one everyone holds up as the paragon of innovation.

I was surprised to learn that Otto didn’t make his great innovation until 1928. By then, we figured out electricity, radios, automobiles and airplanes before someone cracked the code on uniformly slicing bread. To give you some perspective of how recent an invention this was, Betty White is older than sliced bread.

Otto would’ve had his machine ready 11 years earlier, but a fire in his factory destroyed the prototype and his blueprints. So, he introduces his bread slicing machine in 1928, makes millions of dollars and becomes a household name. Right?

Not exactly. In fact, Otto’s invention didn’t take off for five years — after he sold off the patent rights. He hadn’t fully thought through everything needed to bring sliced bread to consumers.

You see, it wasn’t enough to just slice the bread: bread also needed to be banded so it wouldn’t fall apart before it was wrapped up. Another inventor came up with that innovation, and the original machine was intended for home use. It took the Taggart Baking Company to realize that there was a market for slicing bread before it got to the consumer.

Then, there was the marketing of sliced bread. We all know Wonder Bread. They were the first company to distribute sliced bread nationally, and it fundamentally changed how grocery stores displayed their food. But the thread of innovation didn’t stop there.

With the introduction of uniformly-sized bread, pop-up toaster sales exploded and eating habits changed as well. People started clamoring for jams and jellies to spread on their sliced bread, and a relatively new thing called peanut butter became the rage.

All of this happened because Otto Rohwedder made a machine to slice bread – and yet, Otto hardly benefitted at all from his innovation.

Now, let’s say in some fantasy world, Otto was a customer of ours, and it was before we merged with Siemens, made all of our acquisitions and built a holistic digital innovation platform so he could harness the power of digital disruption.

We would have been able to help Otto accelerate the design of his machine by a year or two, and we could’ve introduced him to Teamcenter so that his intellectual property wouldn’t go up in flames. But we may not have considered all the disruptive implications of his innovation.

If Otto had talked to us as we operate today, we wouldn’t have focused solely on optimizing the development of the slicer. We would’ve talked with Otto about the entire lifecycle of the product he was creating—not just the slicing of bread, but how it’s banded together, wrapped, automated, produced, marketed and consumed.

To put it another way, we would’ve made him aware of the entire sliced bread edible thread, and we would’ve worked with him to figure out how he could fully capitalize on digital disruption and his innovation.

This opportunity to think beyond traditional business models is how our customers are changing. For them, digitalization is the greatest thing since sliced bread.

This concludes our discussion on digital disruption in the era of digitalization.

About the author

Bob Jones is the Executive Vice President of Global Sales, Marketing and Services for Siemens PLM Software. He and his team are responsible for the company’s sales, marketing and service delivery on a global basis. He partners with Siemens PLM Software’s zone sales leaders to target geographic, industry and strategic corporate opportunities. Throughout his Siemens career, Jones has held a number of leadership roles in sales and marketing. Before his current position, Jones was the senior vice president and managing director of the Americas and was responsible for sales, sales support and services delivery in North and South America. He has also led sales, sales support and services delivery for the company’s U.S. organization and the company’s global General Motors account. His responsibilities have also included direct and indirect sales and marketing strategies for the PLM portfolio to the automotive OEM and supplier industry. Before joining Siemens PLM as an account executive, Jones began his career in product development at Johnson Controls, Automotive Systems Group (JCI/ASG), where he was a chief engineer responsible for mechanism programs to OEMs in America, Asia and Europe. Jones has a master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Virginia Polytechnic University and a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Western Michigan University.