Computer Aided Engineering in the Industrial Metaverse – Part 4

In Part 3 we showed how a reduced order model (ROM) could be interacted with in an Industrial Metaverse context. That ROM example was built around thermal conduction, where inputs such as applied power could be adjusted in real time. It worked — but it was still a single-physics demonstration.

In this post we go one step further. We’ll show how parametric POD-ROMs can break out of that single physics bubble. With this approach, a ROM extraction approach can be used no matter the physics. Thermal, fluids, electromagnetics, even coupled multi-physics problems — all can be captured and interacted with in real time.

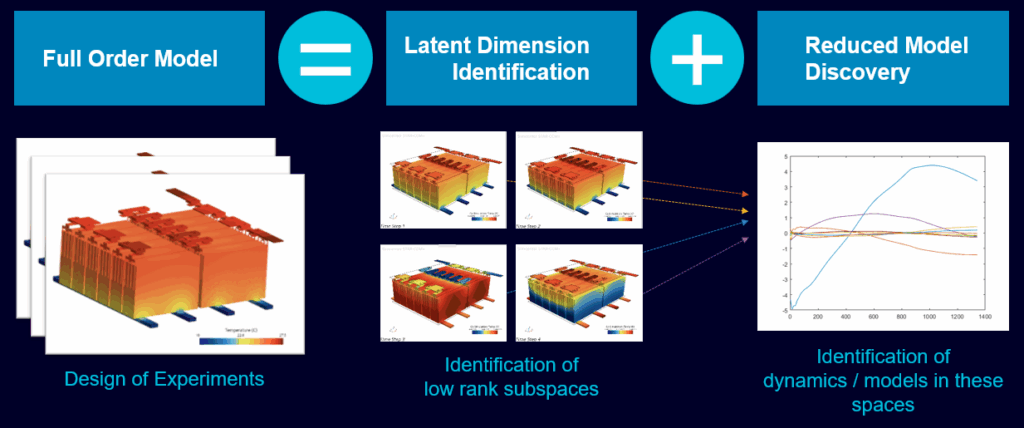

From full order models to reduced spaces

The ROM extraction process starts with a full order model (FOM). That’s the high-fidelity simulation — 3D discretised meshed models, accommodating all relevant physics, and for sure resulting in long runtimes. Running the FOM multiple times provides data so that we can use it as a teacher.

By running a carefully chosen set of simulations (a design of experiments), we collect snapshots of how the system behaves as parameters change. These snapshots hold the key patterns of variation. This includes the transient response behaviour of the system.

With Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD), we then compress those patterns down into a low-dimensional subspace. We discover the smaller set of “shapes” or “modes” that explain almost all of the system’s behavior.

Learning the dynamics from data

Once we have the reduced basis, the next question is: how do states evolve in time? Here we use an approach called Operator Inference. Rather than simply fitting the rate of change from one moment to the next, the model is trained to reproduce the system’s behaviour over many time steps into the future.

This makes the learned dynamics far more stable and tolerant of noisy or limited data — an important feature when training from expensive, high-fidelity simulations. The method retains the interpretability and efficiency of classical polynomial reduced models, but it’s trained using modern differentiable-programming techniques similar to Neural ODEs. In effect, the ROM learns not only what happens next, but how trajectories evolve over time — giving us predictive, physically meaningful reduced models that can run interactively and even faster than real time.

(Readers interested in the underlying mathematics can refer to the formal publication: W. I. T. Uy, D. Hartmann, and B. Peherstorfer, “Operator inference with roll-outs for learning reduced models from scarce and low-quality data,” Computers & Mathematics with Applications, 2023.)

A battery use-case example

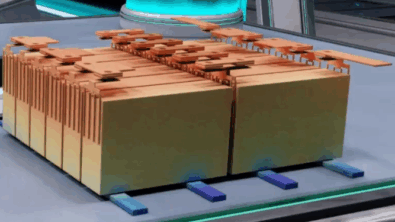

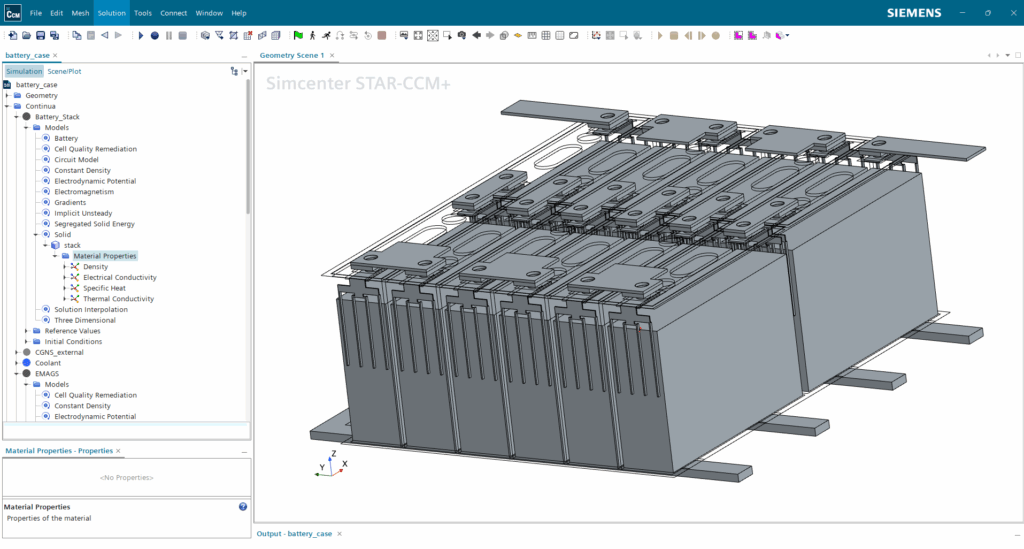

The electrification of mobility relies on electrical energy storage and electrical energy provision. Batteries are used, charged to store energy and then that energy being released to power electric motors. Without getting into the electro-thermo-fluid-chemical multi-physics details, suffice to say that when in use or when being charged, DC electric current is provided by the batteries, the rate at which that electrical energy is provided is a function of the temperature of the batteries as well as how much electrical energy they have left to provide (their State of Charge). A liquid cooling circuit is used to cool the bottom of the battery cells so as to maintain efficiency and reliability.

Such an electro-thermo-fluid-chemical 3D FOM is constructed in Simcenter where electrical current is applied in a charging mode. Charging current and cooling fluid temperature are considered as variable input parameters, the resulting full 3D fields are extracted via a dynamic Design of Computational Experiments approach. Joule heating in the electrical supply network, thermo-chemical response of the battery cells as well as fluid flow and heat transfer in the cooling channels are all considered in a single multi-physics FOM.

Industrial Metaverse interactivity

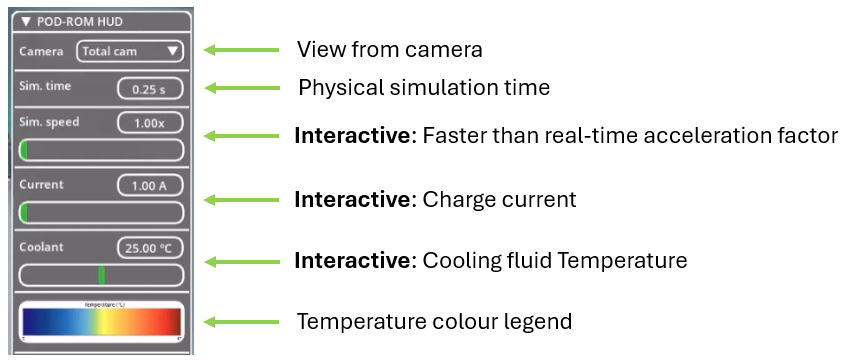

A bespoke Heads-up-Display is implemented in NVIDIA’s Omniverse to enable real-time interactivity with the parametric POD-ROM.

The ‘Sim. speed’ slider bar allows for the interactive simulation to be accelerated to faster than real-time. The thermal time constants of this battery stack are such that the thermal response to changes in either the charging current or inlet cooling fluid temperature would be in the order of 100s of seconds. That would make for a demonstration that requires a lot of patience! The parametric POD-ROM is fast enough though to provide predictions faster than real-time. This is one it’s key attributes, making it applicable for in-operation xDT deployment as part of a predictive control system. In theory capable of knowing what will happen in the future as a function of the current state to allow for control system adaptions to thwart any potential untoward behaviour – before it might otherwise occur. Being able to provide thermal insights at 10000s of un-instrumented points, ahead of time, is its true value.

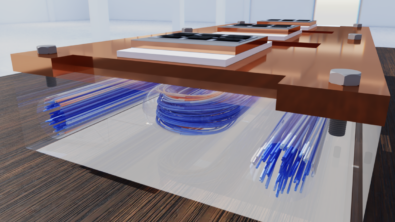

We could have created a virtual Metaverse representation of the end operating environment of the battery, e.g. an EV, but chose instead to put it on a test bench in a kind of futuristic test lab. This allowed us to explore the use of ‘virtual planes’ to show the faster than real-time change in temperature on 3 slices through the battery module (on the left hand side). The horizontal slice is bisects the liquid cooling channels, the other 2 vertical slices bisect the battery cells themselves. This in addition to showing the surface Temperature variation of the battery module itself (on the right hand side):

Metaverse physical-realism

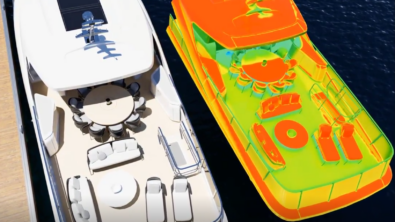

The Metaverse is many things to many people, but at its core it is a virtual representation of the real world. That representation must not only look like reality (photo-realism) but behave like reality (physical-realism). Digital twins are at the heart of that requirement. The above example showcases a parametric POD-ROM technology that enables faster than real-time interaction with an electro-thermo-fluid-chemical model of a battery module, though just showing the resulting thermal behaviour.

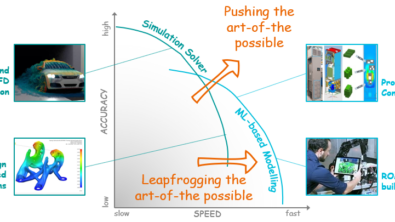

Where next? There is much talk of ‘multi-physics’, be it thermal, fluid, electromagnetic, vibration, stress etc. but in reality there is just ONE physics. Is there a simulation technology today that enables real-time or faster than real-time prediction of all these 3D physical phenomena to engineering grade accuracies? No. We’re still a long way away from being able to immerse ourselves in a virtual reality and prod it, poke it, heat it, bend it, shake it etc. and see the response accurately and immediately. But that is indeed the vision.

Disclaimer

This is a research exploration by the Simcenter Technology Innovation team. Our mission: to explore new technologies, to seek out new applications for simulation, and boldly demonstrate the art of the possible where no one has gone before. Therefore, this blog represents only potential product innovations and does not constitute a commitment for delivery. Questions? Contact us at Simcenter_ti.sisw@siemens.com.