Education, Technology, and Sustainability in Humanitarian Engineering

In the world we live in, the impacts of climate change are becoming more apparent every day. Weather patterns are getting more unpredictable and severe, affecting underserved communities the most. So, what can we do through technology and education to come up with practical and sustainable solutions for these challenges?

This podcast features Alberto Martinetti, an associate professor with a background in mining engineering, and Nikola Petrova, a lecturer with experience in educational science and curriculum development. In this episode, Alberto and Nikola both share their individual motivations for getting involved in the field of Humanitarian Engineering.

In this episode, you will learn about the dynamic intersection of education, technology, and sustainability in Humanitarian Engineering. You will also get to hear more about the commitment of Alberto, Nikola, and the University of Twente to educating engineers who are not only technically skilled but also sensitive to the needs of underserved communities.

In This Episode, You Will Learn About:

- The role of Education in Humanitarian Engineering (03:11)

- The development of a new Master’s Program in Humanitarian Engineering and Pilot Course (04:14)

- Student Feedback and Impact (04:23)

- Challenges and Accreditation of developing a new Master’s course (09:23)

- Siemens’ Tech for Sustainability Campaign (14:13)

- Agribox Concept and How it Helps Combat Issues of Sustainability (16:36)

- The significance of community engagement, practical learning, and sustainable development in engineering education and humanitarian efforts (19:12)

Connect with Alberto Martinetti:

Connect with Nikola Petrova:

Connect with Dora Smith:

Keywords: Humanitarian Engineering, Sustainability, Education, Technology, Climate Change

Podcast Transcript

[00:03] Dora Smith: Welcome to Innovation in the Classroom by the Siemens Empowers Education Team. I’m Dora Smith. We live in a world where the effects of climate change are made apparent every day. Weather patterns are more unpredictable and severe. And it’s people and underserved communities who bear the harshest brunt. So what can we do from a tech and education perspective when it comes to developing sustainable solutions to these types of issues? Two people working directly in this capacity are Alberto Martinetti and Nikola Petrova. Both work within the humanitarian engineering discipline at the University of Twente in the Netherlands, and both are deeply entrenched in developing sustainable tech-forward solutions for communities around the world who need them the most. Alberto is an associate professor with a background in mining engineering and Nikola is a lecturer with a background in educational science and curriculum development. To start off our conversation, I asked them both to explain what it was that made them interested in these respective professional spaces.

[01:05] Alberto Martinetti: I started my bachelor’s and master’s program in 2004 — so, quite some years ago. But definitely what I liked was also the opportunity to work, to boot into developer society, so to speak, from the beginning — from basically the extraction of raw materials, do it in the proper way, in a sustainable way. Even back then, in 2004, 2005, when I started my master’s, the hot topic was definitely already sustainability; how to make it more sustainable in the mining sector.

[01:46] Nikola Petrova: I think, for me, education was always a big topic. I always say, there are a lot of little girls who want to be teachers when they were small. But for me, it actually stayed. So after finishing high school, I started a bachelor’s in education — so primary school education, and something called social pedagogy, which is education for people, mainly for children from disadvantaged families, which I think made the really nice bridge to Humanitarian Engineering. So I would say specifically that I was interested in engineering, as such, but I’m mainly interested in the humanitarian part of engineering, and then it came all together.

[02:24] Dora Smith: So, both Alberto and Nikola now work in the humanitarian engineering space, which is a space that can perhaps be difficult to conceptualize. I asked Alberto what his definition of it was. Here’s what he had to say.

[02:37] Alberto Martinetti: That’s a really big question—I must admit—to answer, but let me start from this point. The world is facing a challenge of increasing complexity everywhere. We do believe that integrated social technical solutions are needed to properly take a humanitarian challenge, and is difficult to access basic needs for hundreds of communities. So, if we want to give a sort of box or definition to Humanitarian Engineering, is how could we support underserved and marginalized communities to get access to basic needs?

[03:11] Dora Smith: Expanding on Alberto’s answer, Nikola broke down what she believes the role of education to be when it comes to humanitarian engineering.

[03:19] Nikola Petrova: The way I see it, I think there are two roles as a higher institution, as a university, for us, one role is, of course, to train future engineers who will have the sustainability in mind, resilience in mind, helping people who are from disadvantaged communities, I think that’s one of the education lines in humanities engineering. And the other one is also helping people from those disadvantaged communities to actually be able to help themselves, to find a way how they can get out of the situations that they are in right now.

[03:58] Dora Smith: Alberto and Nikola are both involved in developing a master’s program in Humanitarian Engineering at the University of Twente. In fact, they have launched a pilot course for it just this spring. They both gave their feedback on how the course went, what the student reaction to it was, and what the content consisted of.

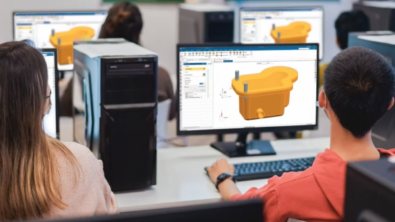

[04:15] Nikola Petrova: I think, in general, from our point of view, it went really good. We got around 20-25 students who were interested in the topic. They all came from different disciplines — so, we had mechanical engineering students, industrial design engineering students, civil engineering, and Sustainable Energy Technology students. And I think they really enjoyed working together in teams. So, we had teams mixed from different disciplines, and they were working on a project which was related to the Agribox — so, helping developing agriculture techniques and learning space for disadvantaged communities. And what we heard so far was the students really enjoyed because this was one of the first courses where they could actually really think of the social impact of their technologies and where they were working in an environment with a lack of resources. So, I think that was innovative for all the students that we had in the class. So, we introduced a couple of lectures, so that was mainly the theory, which was related to various disciplines. So, we had lectures on engineering, on Humanitarian Engineering Design, but we also had lectures on stakeholder management, systems thinking, but also on ethics, for example. And I think this was specifically something that was completely new to all the students. But the majority of the course was indeed related to the project. And I think that our university students are used to working with projects and working in teams. So it was not really something that we had to pay special attention to, to help them to be able to work with students from different disciplines. So, it kind of naturally happened. But as far as we talked with the students, they said that there was an additional level of challenge, not just working in a multidisciplinary team, but also tackling challenges that were multidisciplinary, and they had to know a bit of ethics, a bit of culture, bit of political situations in the countries and so on.

[06:11] Alberto Martinetti: I think, for us, the Course Introduction to Humanitarian Engineering acts as a teaser for the full master’s program that we are developing and for us, was an opportunity to make a trial to get the students exposed to three domains of Humanitarian Engineering that we believe are very important for this field. And so to speak, they are Humanitarian Aid Engineering, so a quick solution for water supply, communication connections, and so on. Long-term planning and capacity building, so if we want to give a word, it’s Resilience Engineering. And lastly, implementation and value creation from technology — so how could we build responsible and sustainable intrapreneurship with job creation, small-scale economy planning, and so on? And we use challenge-based learning in the course to blend together the three domains with the main assignment, the main challenge, that we decided to use in the course, that is the Agribox in this case.

[07:10] Nikola Petrova: So, with this course, it’s master’s students mainly. But as Alberto mentioned, this course that we are just finishing right now, is a teaser for the master’s program that we are planning to launch in, let’s say, 2025. So, this was the first education offering that we started. But for next year, we are also planning a minor in Humanitarian Engineering. And minor, here at the University of Twente means a block of 15 ECs — so, 15 European Credits where students are engaged with a specific topic, in our case, it’s Introduction to Humanitarian Engineering or Humanity Engineering in general, where they work on projects together, where they have lectures. So, something what we have now within the course but on a larger scale, and that again will help us to prepare for the big launch of the master’s program in 2025.

[08:04] Dora Smith: After hearing Nikola and Alberto’s feedback on the course, I was curious as to what inspired them to go down this road. Was it their own passion or perhaps an industry demand that needed to be met?

[08:15] Alberto Martinetti: It’s a mix of things and different requests. Definitely, there is a personal and internal strive for that in order to also provide support and train for underserved communities and marginalized communities. There was a request from our students, actually, to have a greater impact on society; focusing, again, on part of the society that has less advantages. And let’s say, from there, we move and we decided to create also something more structured than small assignments, thesis, and internship, but having something more structured on the more precise educational line that is also equipping students with the right skills in order to take all this type of problems and enlarging the impact of their studies on the society.

[09:10] Dora Smith: Now setting up a credit course can be difficult and complicated without the right support. Nikola and Alberto expanded on what their experience was with their course and the support they received from the university.

[09:22] Alberto Martinetti: The University of Twente in general was very much supportive. It gave a lot of resources in terms of staff and in terms of strategy and policy department. But definitely, it’s a difficult process when you want to set up a full new master’s program. Of course, different countries have different ways to give accreditation to a master’s program. I would say that in most of the countries in Europe, you have to refer to the ministry in order to have a new master’s program with an accreditation, and this is exactly the phase in which we are at the moment. So, we are submitting to the ministry the proposal that we have for the master’s program, and, of course, they always are very strict on some parameters, especially on the labor market because it’s important also from our side to be sure that whenever we deliver humanitarian engineers, they are able to find a job position somewhere, either in our country—so, in the Netherlands—or in general, on a larger scale in the world. So, there are some requirements that we have to match.

[10:31] Nikola Petrova: It’s hard, I think, to get a master’s program accredited, but we have great support at the university. So, we have the deans of three faculties who are fully supporting us. As Alberto mentioned, we have a lot of support, also, when it comes to people and resources. And I think I’m also one of the examples because I got hired very recently, and only thanks to the fact that there was support from the faculty to hire somebody like me, to help Alberto and our colleagues who are working in Humanitarian Engineering.

[10:59] Dora Smith: Another difficulty that presents when setting up a course for the first time is curriculum development. This is particularly true when you don’t have other courses to emulate or resources to pull from. I wondered whether this was the case for Alberto and Nikola’s course.

[11:13] Alberto Martinetti: Everything starts, usually, from an idea, and then you try to move from there. And this is exactly what would happen also for us. We start also looking around us; how are the other universities offering similar programs, if there are other universities that are offering similar programs, both in Europe and overseas, like in the US, Australia, and in other parts of the world? And then we start creating your first draft. And also to try to look at what the others are doing. What is the trend in the industry? What is the trend for the organization that we’re working on in Humanitarian Engineering? What are the important elements that you have to pull in, in order to provide competent professionals in this case? And we look at also quite a lot at the US. Because in the US, even if maybe there are not that many full master’s programs, but there are a lot of master’s courses or undergraduate programs that are working on similar topics on Humanitarian Engineering, Developing Engineering, and so on and so forth.

[12:21] Dora Smith: Early this year, Alberto and Nikola participated in Siemens’ Tech for Sustainability Campaign, a global initiative that encouraged students, professors, startups, and the like, to find tech-enabled solutions to the sustainability issues we’re facing in the world today. They were part of the “Educating for Sustainability” challenge where they developed an idea that aims to address the challenges of growing populations in underserved communities who lack access to basic resources. Their idea was to prepare future engineers to support underserved and marginalized communities with the use of technology, in this case, the Agribox. The Agribox is an evolution to the EDUbox — a self-contained, off-grid, and modular learning environment, acquired by Alberto and his colleagues to provide technical, vocational education and training to underserved communities. Alberto and Nikola talked a bit about how they heard about the campaign and their experience participating in the challenge.

[13:21] Alberto Martinetti: Well, actually, it was quite funny because I received a text message from a friend, and she told me, “Look, there is a part of Siemens that is launching this sustainability tech campaign, and there is a specific challenge on education for sustainability.” And I started reflecting like, “Let’s see if there is some possibility there.” And we started looking in the call with Nikola and I said, “Yeah, maybe we have some opportunity over there.” So, we try to create an application that could be well-received and can fit in the requirements of the campaign from Siemens. And actually, it went pretty well.

[14:09] Nikola Petrova: A couple of months later, we traveled to Germany, to Munich. And it was really nice three days meeting people from Siemens. We were also in the Siemens headquarters, which I think, at least for me, was a very nice experience. And when we were further developing the idea, we got one Siemens employee, which was very rare because most of the teams got students who were helping them to develop the idea. But in our case, it was a Siemens employee who wanted to be part of the challenge, who really helped us to further develop the idea we had, not in terms of education, but more from the technical perspective, which also helped us quite a lot during the final pitch. So, I think it was a really great experience to also meet people who work in different fields, who pitch their final ideas on different topics, and connect and see how all of us are passionate about certain topics and made it all the way to the final pitches in front of the management team of Siemens being broadcasted online. So, for me, at least, I was very stressed that day, I remember. Because they give you a microphone, they tell you, “Okay, this is the foyer. Here you need to present.” I think the presentation was for five minutes. So, for me, it was my first experience pitching in front of such an important audience. But it was great, I must say, it was great.

[15:33] Dora Smith: What stood out to me the most when I first heard Alberto and Nikola’s challenge presentation was their focus on three sustainability goals, instead of just one. They have built something to address poverty, hunger, and education access, and not just to address them, but also to hone in on solutions with technical feasibility. I asked them what they wanted the main takeaway to be from their presentation.

[15:58] Nikola Petrova: I think there are Sustainable Development Goals, the three of them that you mentioned, I think that’s the core of our work. I think we work with them every day. And these are the most fundamental goals that we think need to be fulfilled, met, or improved, let’s say, if we want to make the underserved communities and marginalized communities, if we want to improve their life and well-being.

[16:19] Alberto Martinetti: SDG number one was no poverty. I think there was zero anger. I think number two SDG and then the quality of education because there are the three SDGs that, for us, both as academics, but also as a passionate humanitarian engineer play an important role indeed.

[16:36] Dora Smith: I spoke briefly about the Agribox before, but I wanted to know what exactly it was, how and why it was developed and how it will work to combat issues of sustainability in underserved communities. Alberto and Nikola broke it down for me.

[16:49] Alberto Martinetti: The Agribox is the second iteration of the EDUbox. The EDUbox is a design and engineering realized by us at the University of Twente as a portable and off-grid learning environment. The first EDUbox has been deployed at the moment in Jordan, in cooperation with Yarmouk University, in order to bring access to education to refugee camps there in Jordan, close to the Syrian border and with Palestine. The EDUbox has been realized also with the support of Norfolk that is part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Netherlands, they provide us with a grant. And after that, we start thinking, “Okay, the EDUbox has a generic purpose at the moment. We want to focus on the different disciplines within the EDUbox.” And one of that is the EDUbox related to agricultural study, and we call it Agribox, and it’s one that we try to develop also through the support of Siemens. Agribox basically wants to bring sustainable agriculture techniques to low-income countries. As I said before, the Agribox aims to take SDG number two — so, zero anger — achieving food security, improving nutrition, and empowering small-scale farmers. Our idea which we are still also working on, by the way, is the Agribox will help farmers to learn and apply innovative and effective crop methodology. It will provide environment for agricultural education, it can be portable and adaptable to different locations, it will have space for brainstorming areas, and resilience growing matters can be taught in the Agribox. At the moment, as Nikola said before, it’s at the concept level. We have also scaled the model, already realized, and the next step is to realize a full-scale Agribox to deploy in one of the areas, as we did with the EDUbox last year. Thanks to Siemens, we use the Simcenter Amesim in order to test and simulate some of the features of the Agribox — like the temperature inside the container and which type of insulation we should look at. Also, other features related to the energy system because that has to be off grid, so we have also to produce energy. So, I think we, through also the sustainability campaign, we were able to make a big step ahead for the design and engineering of the Agribox.

[19:21] Dora Smith: So when we look at developing solutions, like the Agribox, how does a solution like this develop in the classroom setting and how is classroom content structured to put students in the right mindset?

[19:33] Nikola Petrova: In general, it needs to be hands-on. I think there’s something that we realized also during the course but also when, for example, deploying the EDUbox right now. So, it’s very important if education at our university, but also when we want to, for example, use Agribox, it needs to be hands-on. Because if we use lectures, if we use just frontal education, that’s not really the way to do it because people really need to test it. There’s also something that our students at the University of Twente really appreciate. So, what is also our next step, we really want to have students going abroad, having internships abroad, and working together with the communities because now in the course that we were just running, we, of course, had the providers of the case who were in close contact with the communities, but still the communities at this moment were not yet involved. And we really think this is something that we want to improve in the next years because the students are asking for it, and it will really benefit the outcomes that they will develop.

[20:34] Dora Smith: I asked Alberto and Nikola about the scalability of the Agribox and EDUbox and what countries they are collaborating with, or hope to collaborate with, on them.

[20:44] Alberto Martinetti: We have different contracts with several countries, also in the sub-Saharan part of Africa. We are in contact with two institutions in Kenya that actually are really interested to have an iteration of this type of project like the EDUbox. We recently went to Ethiopia and Uganda for an Erasmus Plus project that we had with the two universities over there. And we established good cooperation with them, both for this type of project, like EDUbox-related, but also for having students assignments or having student teams that can work together on humanitarian challenges. And of course, at the moment, we are looking at different types of funding mechanisms in order to support the next iteration, for example, of the EDUbox or other projects that we want to introduce in the course of the university.

[21:35] Dora Smith: And of course, when developing tech solutions and, in this case, collaborating with communities on a global level, there are always growing pains and lessons learned. I wondered what these were for the Agribox and EDUbox.

[21:48] Nikola Petrova: I think, maybe the one that I already mentioned is the community involvement. The very important thing is that it’s not a product that we deliver to them, and we say, “Hey, we are the University of Twente. This is what we made for you. Use it because it’s really good.” I think it needs to really come from the communities that have the need or they really want something new and they are just asking for additional support but they need to be the owners, let’s say, and the owners who actually feel the ownership of the innovation that will be deployed there. Another lesson learned for me is the culture. You might think that you know the cultural differences, you’re aware of the cultural differences. But I think once you travel to such countries with completely different cultures, you realize that the gap or the difference between the culture is so huge, and you really need to not only try to understand their culture but also maybe change your values, your beliefs, and your culture to find a common ground for all of you to work together. We are also learning — I don’t want to say that we know how to do it – we’re also learning.

[23:01] Alberto Martinetti: I think the lessons learned that you mentioned are really true and sometimes are also shocking. Even though you think that you are prepared for that, but it’s never the case. But I also like what you said about community-based learning and community-based research because it is also one of the parts we are trying to introduce in the program is the importance of community-based learning as a strategy to integrate meaningful community engagement with instructional reflection and to enrich the learning experience of the students. We found that this is extremely important, and is a two-way street, by the way.

[23:43] Dora Smith: Looking forward to the future, and knowing what they know, I asked Alberto and Nikola to break down what they think the outcomes of Agribox and EDUbox will be and whether they foresee expansion on the horizon.

[23:55] Alberto Martinetti: We should not be too much interested in the big numbers. What we should be interested is to be able to provide a learning environment with meaning and with an impact. So we should not, in my opinion, go for mass production, but we should focus on the quality and on the impact that each of EDUbox can have in a community. That is the real deal, if we want, using of these EDUboxes; how many people you can reach instead of having, “Okay, we will produce 200 boxes in the next year, and we can deploy it in different parts of the world in different underserved communities.” We should really look at how big is the impact, and how can the living condition improve using the boxes.

[24:44] Nikola Petrova: I think Alberto said it really nice. I think it’s not about having many EDUboxes, but I think it’s about having a lot of learning environments, whether it’s in already existing buildings or environments, or whether we need to bring something there to help. So, I think it’s just to give as many opportunities for people to learn and to get more opportunities in their lives. At least that’s the way I see it.

[25:10] Dora Smith: Finally, I asked Alberto and Nikola whether they had any other thoughts or comments that they wanted to emphasize about the tech sustainability challenge. Here’s what they had to say.

[25:20] Alberto Martinetti: I think we also reflect a bit after the pitch, after the challenge, after the campaign. I think what we would really like to try to build is sort of the next phase, not only for the EDUbox, but in general for how could we engage more the industrial partners in showing that there is a possibility and there is—also, if we want—business opportunities in part of the world and part of the community that maybe are not the primary target for companies. If we can start from there and if we can show that there is a supporting business model, I think a lot of steps, a lot of good things can be done in that regard to access to basic needs in a sustainable and also financial way.

[26:12] Nikola Petrova: I was thinking, at this one, I am so heavily involved in education, which is a very big topic for me specifically when it comes to the master’s program. And I was now thinking what Alberto said that indeed every day and every week, we always need to mention to people why it makes sense to have such a program, which also comes with awareness of business models. As you said, we are getting questions about, “Okay, well, your graduates in the future, will they find jobs?” And we are saying, “Yes, they will.” But as Alberto said, if there’s additional support and we really show there is a network for Humanitarian Engineering graduates, that would be beautiful.

[26:55] Dora Smith: A big thank you to Alberto and Nikola for taking the time to speak to me and offering such valuable insight on sustainability in technology and the work being done to make all aspects of engineering humanitarian-forward. This has been an Innovation in the Classroom episode, thank you for listening. Stay tuned to Innovation in the Classroom wherever you do podcasts. I’m Dora Smith. Thanks so much for listening!